REM KOOLHAAS, UNA PERSONALITA’ POLIEDRICA – Prima parte – A MULTI-FACETED PERSONALITY – Part One

Rem Koolhaas è tra i più influenti, e forse discussi, liberi pensatori e teorici dell’architettura moderna.

Concetti come ‘città’, ‘strada’, ‘identità’ e ‘architettura’ appartengono al passato. Il passato è troppo piccolo per poterci vivere dentro. Rem Koolhaas

La cifra stilistica di Rem Koolhaas non è mai troppo definibile, non ha un unico fil rouge riconoscibile, lui stesso non si definisce decostruttivista, anche se è uno dei padri fondatori di questa corrente. [https://www.giusybaffi.com/decostruttivismo-architettura-spazio-in-evoluzione/]

A volte guarda, pur con un occhio nuovo, al razionalismo modernista come nel caso di Villa dall’Ava, altre volte al decostruttivismo, con l’eliminazione totale delle linee ortogonali.

La sua architettura si basa essenzialmente su elementi plastici, frazionamenti, rotture dello spazio, in una sorta di visione spaziale.

Nelle sue opere Rem Koolhaas concede nulla al dettaglio architettonico, le finiture devono essere rozze, l’illuminazione derivata da quella industriale. L’architettura, per lui, deve essere in funzione all’idea da cui è stata generata.

Rem Koolhaas nasce a Rotterdam nel 1944, nel 1968 si iscrive alla Architecture Association School a Londra. Nel 1972 riceve una Harkness Fellowship per fare ricerca negli Stati Uniti. Studia con O. M. Ungers alla Cornell University per un anno, e nello stesso periodo diventa visiting professor all’Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies a New York.

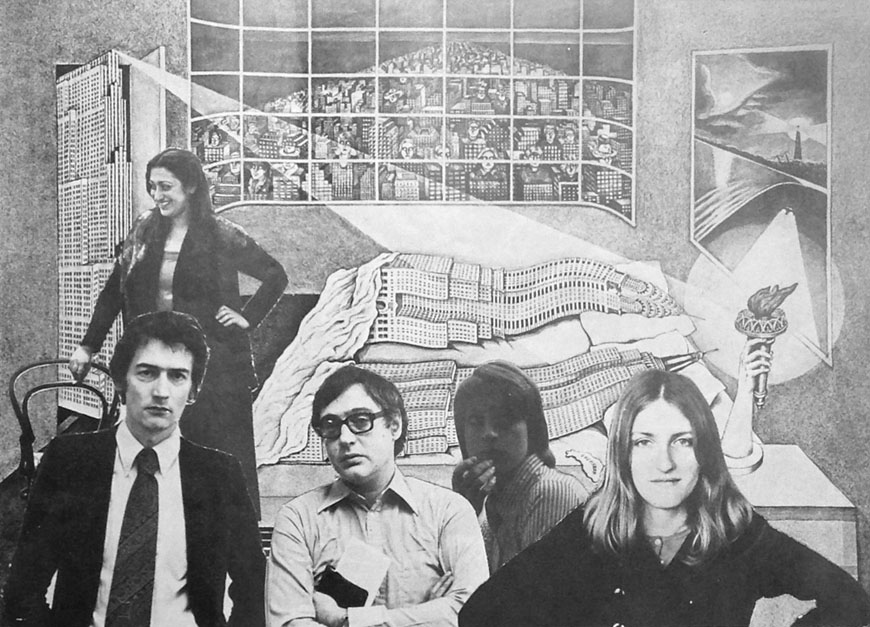

Nel 1975 fonda a Londra lo studio Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), insieme a Madelon Vriesendorp, Elia e Zoe Zenghelis nel quale iniziano a lavorare, giovanissimi, futuri grandi architetti come Zaha Hadid, Winy Maas di MVRDV, Kunlé Adeyemi e Bjarke Ingels. Da allora tutti i progetti di Rem Koolhaas portano la firma dello studio OMA.

Rem Koolhaas is among the most influential, and perhaps controversial, free thinkers and theorists of modern architecture.

Concepts like ‘city’, ‘street’, ‘identity’, and ‘architecture’ belong to the past. The past is too small to live inside. Rem Koolhaas.

Rem Koolhaas’ stylistic signature is never too definable; he doesn’t have a single recognizable thread. He doesn’t even define himself as a deconstructivist, although he is one of the founding figures of this movement. [https://www.giusybaffi.com/decostruttivismo-architettura-spazio-in-evoluzione/]

At times, he looks, even with a new eye, at modernist rationalism, as in the case of Villa dall’Ava; other times, he turns to deconstructivism, with the total elimination of orthogonal lines.

His architecture is essentially based on plastic elements, fragmentations, ruptures of space, in a kind of spatial vision.

In his works, Rem Koolhaas gives nothing to architectural detail; finishes must be rough, illumination derived from the industrial one. Architecture, for him, must be in service to the idea from which it was generated.

Rem Koolhaas was born in Rotterdam in 1944; in 1968, he enrolled at the Architecture Association School in London. In 1972, he received a Harkness Fellowship to conduct research in the United States. He studied with O. M. Ungers at Cornell University for a year and during the same period became a visiting professor at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York.

In 1975, he founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) in London, together with Madelon Vriesendorp, Elia, and Zoe Zenghelis. Young architects like Zaha Hadid, Winy Maas of MVRDV, Kunlé Adeyemi, and Bjarke Ingels started working there. Since then, all of Rem Koolhaas’ projects bear the signature of the OMA studio.

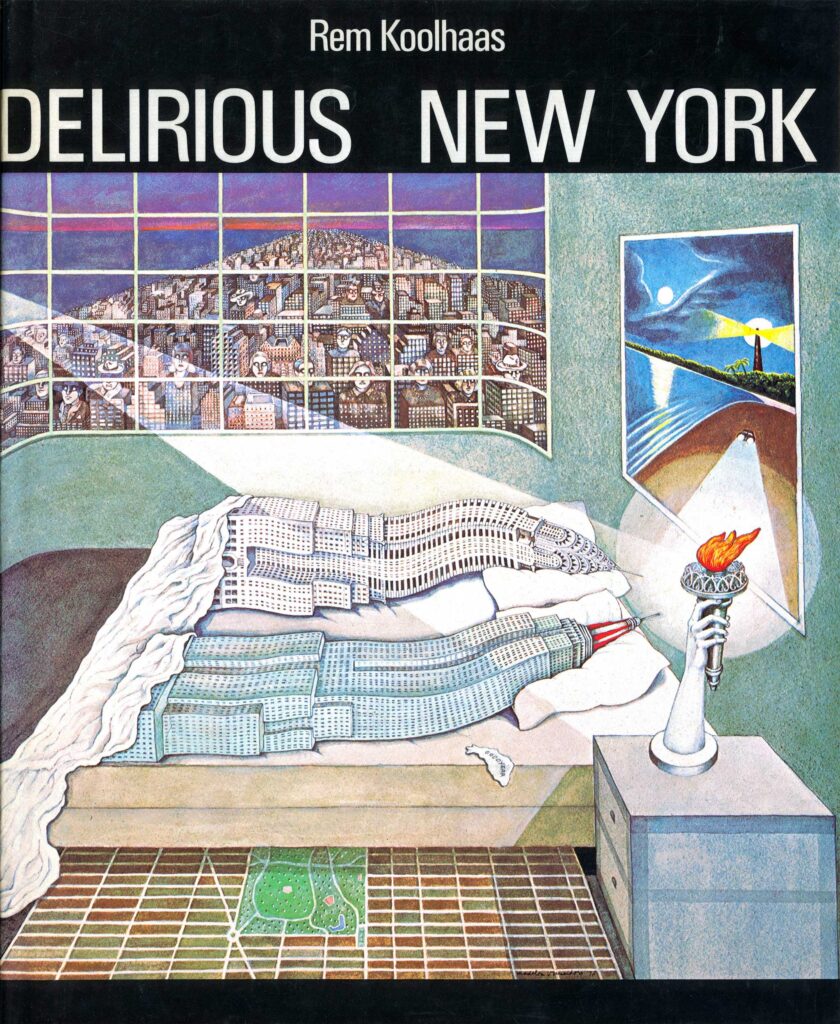

Rem Koolhaas è una persona i cui interessi spaziano dallo studio di nuove forme del vivere comune nelle città occidentali, dall’attrazione per la modernità (espressi ad esempio nel suo fondamentale saggio Delirious New York), alla danza, al teatro, alle arti visive, alle molte culture “esotiche” che popolano le città portuali come Rotterdam, la sua città natale.

Nel 1978 scrive il suo saggio “Delirious New York” da lui descritto come un “manifesto retroattivo per Manhattan”.

In questo saggio Koolhaas racconta di come, nonostante una mancata pianificazione urbana di tutta l’area urbana di Manhattan, il tutto abbia dato forma ad una contemporaneità di sofisticata bellezza, mai raggiunta dagli architetti del Movimento Moderno con le loro utopie metropolitane di cui il grattacielo, tipico dell’edilizia di Manhattan, ne è infatti l’antitesi.

Rem Koolhaas is a person whose interests range from studying new forms of communal living in Western cities to an attraction for modernity (expressed, for example, in his fundamental essay “Delirious New York”), to dance, theater, visual arts, and the many “exotic” cultures that populate port cities like Rotterdam, his hometown.

In 1978, he wrote his essay “Delirious New York,” which he described as a “retroactive manifesto for Manhattan.”

In this essay, Koolhaas recounts how, despite the lack of urban planning for the entire urban area of Manhattan, it all has shaped a contemporaneity of sophisticated beauty, never achieved by the architects of the Modern Movement with their metropolitan utopias, of which the skyscraper, typical of Manhattan’s architecture, is indeed the antithesis.

Riprendendo quindi lo spunto da una visione originale di Manhattan con una sua trasformazione in senso fantastico, Koolhaas si pone come obiettivo di innestare su una metropoli esistente e dequalificata una riorganizzazione con degli edifici che possano trasformarsi in icone anche dal punto di vista visivo.

Immagina di dividere Manhattan con una griglia ortogonale in cui ciascuno isolato ha un edificio iconico con delle forme differenziate in modo che ogni quartiere possa avere una sua identità ben definita.

Da questo concetto di Bigness deriva tutta la sua architettura, per Koolhaas un edificio non deve relazionarsi al suo contesto ma deve, per la sua originalità e per la sua forma caratteristica, diventare un elemento di punta del costrutto urbano e catalizzare l’attenzione trasformandosi in un’icona che caratterizza il quartiere.

In questo modo assurge al concetto rivoluzionario Fuck the contest, dove l’edificio deve imporsi per se stesso e per le sue qualità intrinseche sia nelle dimensioni che nelle visioni utopiche.

Taking inspiration from an original vision of Manhattan and transforming it in a fantastical sense, Koolhaas aims to graft a reorganization onto an existing and declassified metropolis with buildings that can become icons from a visual standpoint as well.

He envisions dividing Manhattan with an orthogonal grid where each block has an iconic building with distinctive forms, allowing each neighborhood to have its well-defined identity.

From this concept of “Bigness,” his entire architecture stems. For Koolhaas, a building should not relate to its context; rather, due to its originality and distinctive form, it should become a focal element of the urban fabric, capturing attention and transforming into an icon that characterizes the neighborhood.

In this way, he embraces the revolutionary concept of “Fuck the contest,” where the building must assert itself based on its inherent qualities, both in terms of size and utopian visions.

«New York è riuscita a produrre la cultura della congestione e, inoltre, è riuscita a esprimere la tecnologia del fantastico, un ideale che forse ha poco a che vedere con le regole della composizione architettonica ma che, in effetti, riesce a produrre manufatti edilizi certamente non meno interessanti di quelli che escono dalle accademie, vecchie o nuove, delle nostre scuole di architettura.» Rem Koolhaas

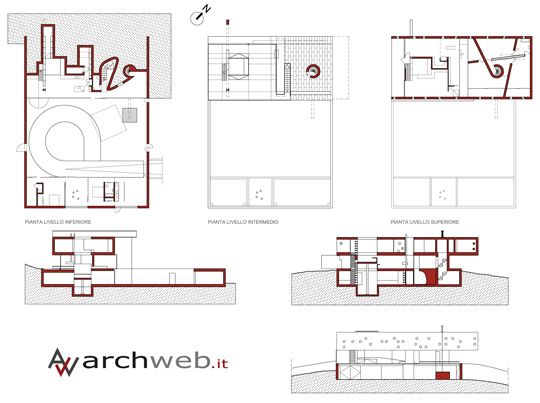

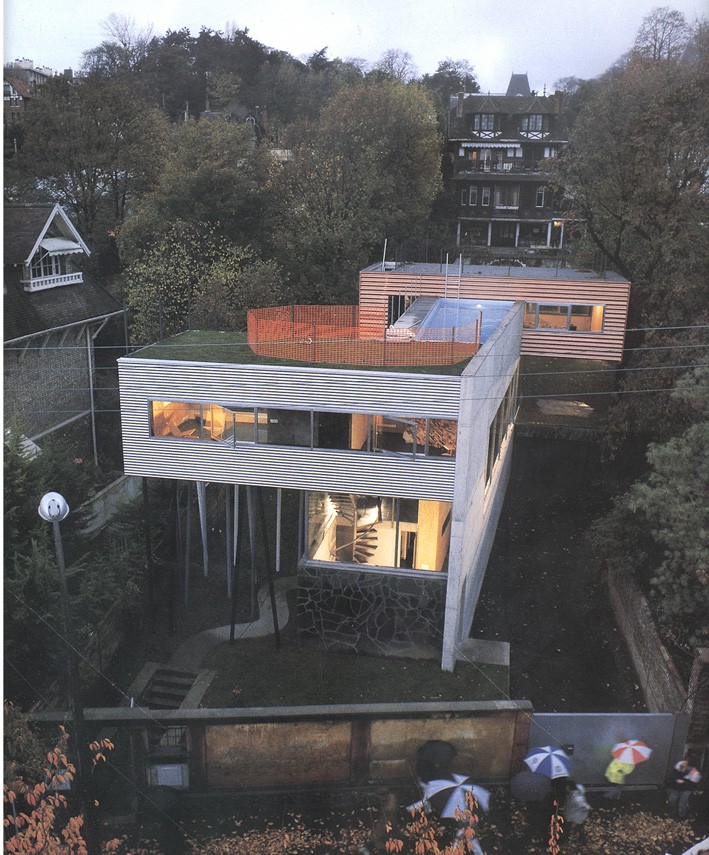

Rem Koolhaas mette in pratica la teoria denunciata in Delirous New York con il progetto di Villa dall’Ava (1985-1991) a Saint Cloud situata nella periferia Ovest di Parigi.

Commissionata per far coincidere l’esigenza di un edificio che contenesse due appartamenti distinti, uno per i genitori e l’altro per la figlia, la casa doveva essere leggera sopra il terreno, con una promenade interna e fortemente permeabile alla luce del sole e con un requisito fondamentale: una piscina sul tetto da cui poter ammirare in lontananza la Tour Eiffel.

“New York has managed to produce the culture of congestion and, furthermore, it has managed to express the technology of the fantastic, an ideal that perhaps has little to do with the rules of architectural composition, but which, in fact, succeeds in producing architectural artifacts certainly no less interesting than those that emerge from the academies, old or new, of our architecture schools.” – Rem Koolhaas

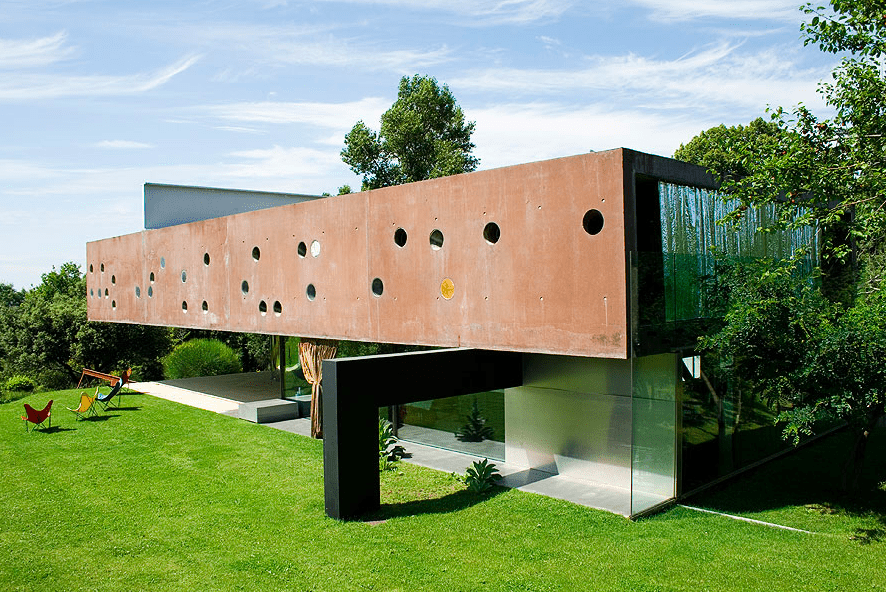

Rem Koolhaas puts into practice the theory outlined in “Delirious New York” with the Villa dall’Ava project (1985-1991) in Saint Cloud, located in the western suburbs of Paris.

Commissioned to accommodate the need for a building containing two distinct apartments, one for the parents and the other for the daughter, the house had to be elevated above the ground, with an internal promenade and highly permeable to sunlight, and with a fundamental requirement: a rooftop swimming pool from which one could admire the Eiffel Tower in the distance.

In questa “casa-manifesto” è evidente il rimando alla Villa Savoye a Poissy di Le Corbusier. Come nella Villa Savoye, Villa dall’Ava è sorretta da esili pilotis, ma questa volta inclinati, la facciata è ritmata da finestre a nastro, la pianta libera è coperta da un tetto giardino.

In this “manifesto-house,” there is a clear reference to Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye in Poissy. Just like in the Villa Savoye, Villa dall’Ava is supported by slender pilotis, but this time they are inclined. The façade is rhythmically punctuated by ribbon windows, and the open plan is covered by a rooftop garden.

Come a Poissy un camminamento inclinato distribuisce gli ambienti interni, ma a differenza della Villa Savoye il percorso non ricrea una ideale continuità tra interno ed esterno, ma unisce trasversalmente i due distinti appartamenti.

I volumi sospesi su elementi a piano terra sono completamente vetrati (argomento al quale ritorna spesso) dando la sensazione di una costruzione galleggiante.

A differenza di Le Corbusier, Koolhaas introduce materiali poveri come le lamiere, in una sorta di rifiuto dell’architettura aulica del razionalismo e introduce una dinamicità che Le Corbusier non aveva, dinamicità percepibile nelle varie parti dell’edificio dove si hanno sempre delle angolazioni visive completamente diverse, nella concezione tipica del decostruttivismo.

Similar to Poissy, an inclined pathway distributes the interior spaces in Villa dall’Ava, but unlike the Villa Savoye, this pathway doesn’t create an ideal continuity between interior and exterior; instead, it transversely connects the two distinct apartments.

The volumes suspended on ground-level elements are entirely glazed (a topic to which Koolhaas often returns), giving the sensation of a floating construction.

In contrast to Le Corbusier, Koolhaas introduces humble materials like sheet metal, in a sort of rejection of the grand architecture of rationalism, and introduces a dynamism that Le Corbusier didn’t possess. This dynamism is evident in various parts of the building, where there are always entirely different visual angles, in line with the typical concept of deconstructivism.

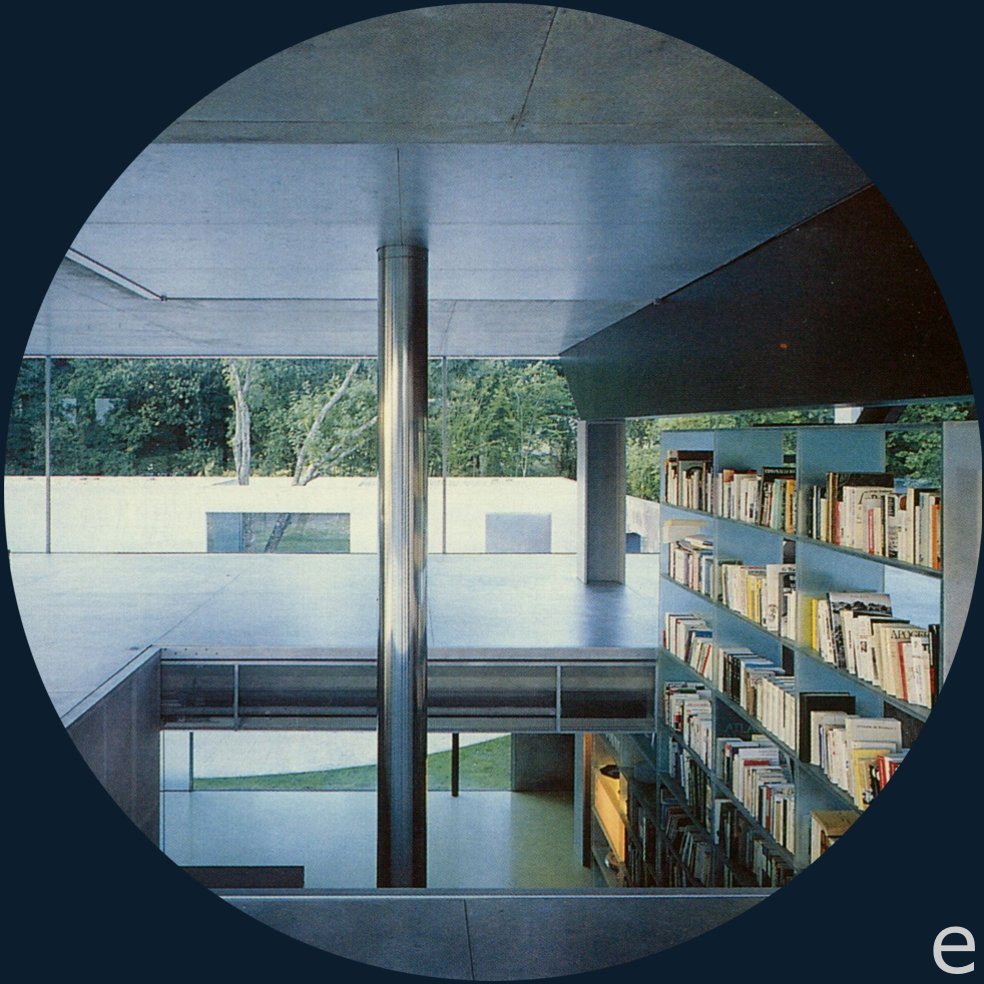

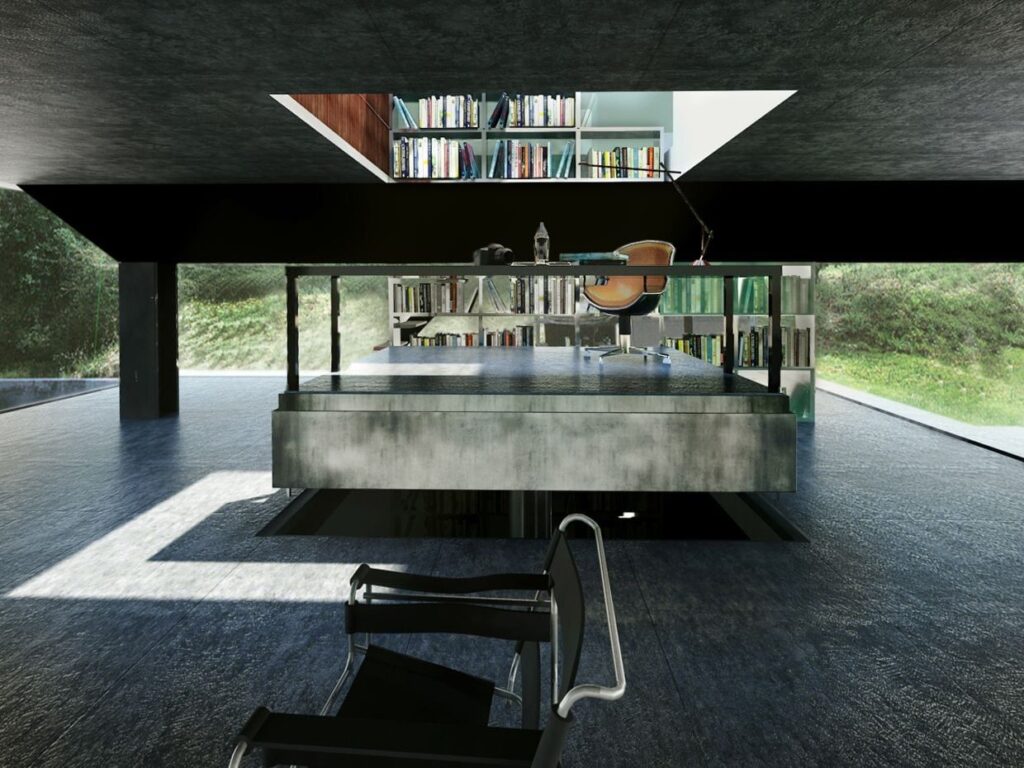

Nel 1994 Rem Koolhaas, firmando sempre come studio OMA, viene incaricato di progettare un’abitazione a misura del padrone di casa, rimasto paralizzato a causa di un grave incidente stradale.

Contrariamente all’idea di un’abitazione a un solo piano, Koolhaas propone la Maison à Bordeaux, una casa a tre livelli. Il piano terra, semi-scavato nella collina, ospita la cucina e la sala televisione, le camere sono al piano superiore. Al centro dei due livelli si trova il soggiorno completamente vetrato da cui si può ammirare la valle del fiume Garonna e lo skyline di Bordeaux.

In 1994, Rem Koolhaas, still signing under the OMA studio, was tasked with designing a home tailored to the homeowner, who had been paralyzed due to a serious road accident.

Contrary to the idea of a single-story home, Koolhaas proposed the Maison à Bordeaux, a three-level house. The ground floor, partially buried in the hillside, houses the kitchen and the television room, while the bedrooms are on the upper floor. At the center of the two levels is the fully glazed living room, from which one can admire the Garonne River valley and the Bordeaux skyline.

Per accedere a tutti i livelli in sedia a rotelle, Koolhaas ha proposto una piattaforma elevatrice 3×3,5m che si muove liberamente in verticale tra i tre piani, diventando parte della zona giorno, della cucina o trasformandosi in un intimo spazio ufficio e garantendo l’accesso ai libri posti su scaffali in policarbonato che si estendono dal piano terra fino alla parte superiore della casa, alle opere d’arte e alla cantina. In pratica un cuore meccanico, una stanza mobile arredata come luogo di lavoro che scorre nello spazio centrale di tutta la casa.

To provide wheelchair accessibility to all levels, Koolhaas proposed a 3×3.5m lift platform that moves freely in a vertical direction between the three floors. This platform becomes a part of the living area, the kitchen, or can transform into a private office space, ensuring access to books placed on polycarbonate shelves that extend from the ground floor to the top of the house, as well as to artworks and the cellar. Essentially, it’s a mechanical heart, a mobile room furnished as a workspace that glides through the central space of the entire house.

Altre piattaforme si muovono in orizzontale scoprendo di volta in volta la vista sul fiume Garonna, sul cielo o sulle colline di Bordeaux.

Other platforms move horizontally, revealing the view of the Garonne River, the sky, or the hills of Bordeaux one after the other.

[…] continua: https://www.giusybaffi.com/rem-koolhaas-una-personalita-poliedrica-seconda-parte/

Rif.: www.archdaily.com www.theguardian.com

Bibliografia:

Rem Koolhaas, Elements of Architecture – Taschen

Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, S, M, L, XL – The Monacelli Press

Roberto Gargiani, REM KOOLHAAS/OMA – Editore Laterza

A.A.AV.V. Editoriale Domus

©Giusy Baffi 2020

© Le foto sono state reperite da libri e cataloghi d’asta o in rete e possono essere soggette a copyright. L’uso delle immagini e dei video sono esclusivamente a scopo esplicativo. L’intento di questo blog è solo didattico e informativo. Qualora la pubblicazione delle immagini violasse eventuali diritti d’autore si prega di volerlo comunicare via email a info@giusybaffi.com e saranno prontamente rimosse oppure citato il copyright ©.

© Il presente sito https://www.giusybaffi.com/ non è a scopo di lucro e qualsiasi sfruttamento, riproduzione, duplicazione, copiatura o distribuzione dei Contenuti del Sito per fini commerciali è vietata.

© The photos have been sourced from books, auction catalogs, or online and may be subject to copyright. The use of images and videos is solely for explanatory purposes. The intent of this blog is purely educational and informational. If the publication of images were to violate any copyright, please communicate this via email to info@giusybaffi.com, and they will be promptly removed or the copyright © will be cited.

© The present website https://www.giusybaffi.com/ is not for profit, and any exploitation, reproduction, duplication, copying, or distribution of the Site’s Content for commercial purposes is prohibited.