IL MONDO DELL’ILLUSTRAZIONE E DELLA PUBBLICITA’ DEL PRIMO ‘900 – THE WORLD OF ILLUSTRATION AND ADVERTISING IN THE EARLY 1900s.

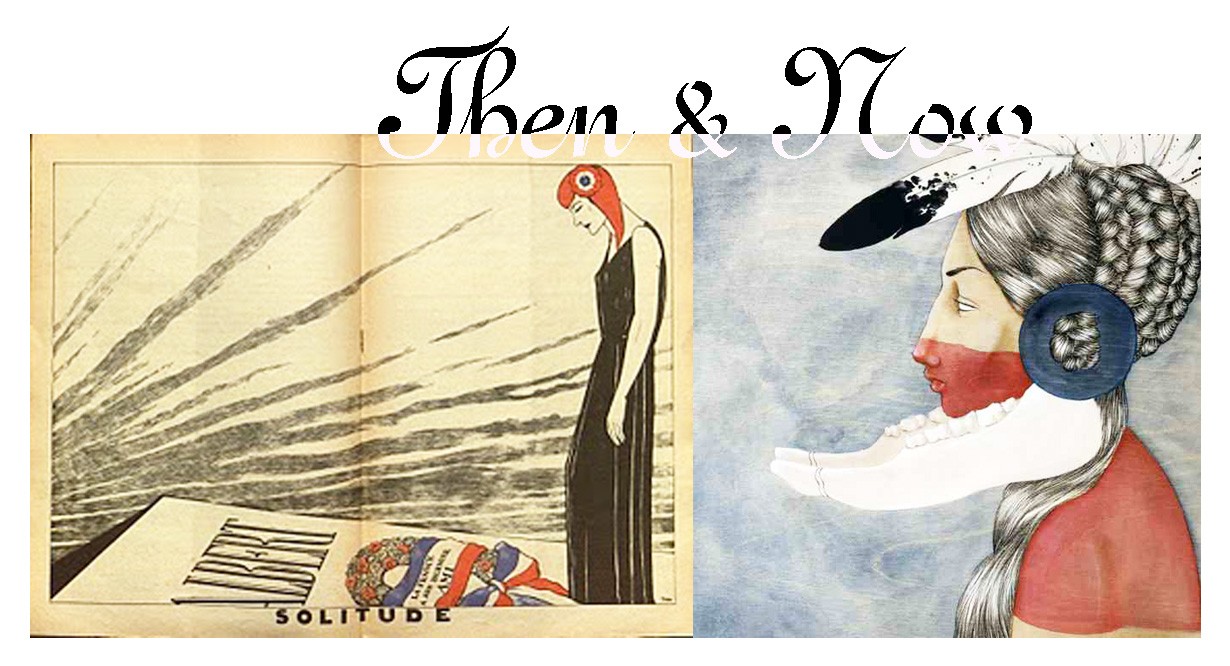

Il ‘900, universalmente considerato il periodo dei grandi illustratori, è anche definito come l’epoca d’oro dell’illustrazione.

Per riuscire a capirne l’importanza occorre fare un passo indietro, quando il manifesto futurista del poeta e drammaturgo italiano Tommaso Marinetti, pubblicato dal quotidiano francese Figarò il 20 febbraio 1909, diventa il primo atto formale e pubblico di questa nuova epoca. Viene inneggiata la civiltà industriale, esaltando il tema della metropoli moderna sede di una vita accelerata e concitata, ricca di stimoli sensoriali e intellettivi. Una vera dichiarazione di guerra alla cultura tradizionale e classicheggiante. I padri fondatori di questa nuova visione dell’arte sono Boccioni, Carrà, Russo, Severini.

A seguito di quest’onda molti artisti si rendono conto di quanto sia importante il fiancheggiamento artistico ai settori produttivi al fine di diffondere un certo modo di scrivere e di dipingere senza il timore di infangarsi lavorando anche per la pubblicità.

Da questa constatazione deriva l’estendersi di criterio dei canoni artistici in ambiti popolari quali la moda, l’arredamento, la pubblicità.

LA MODA E LE RIVISTE

Un settore particolarmente presente in questo periodo è rappresentato dalla decorazione di libri e riviste.

Libri illustrati ma anche riviste e giornali diventano rapidamente una delle palestre più importanti per pittori e giovani artisti.

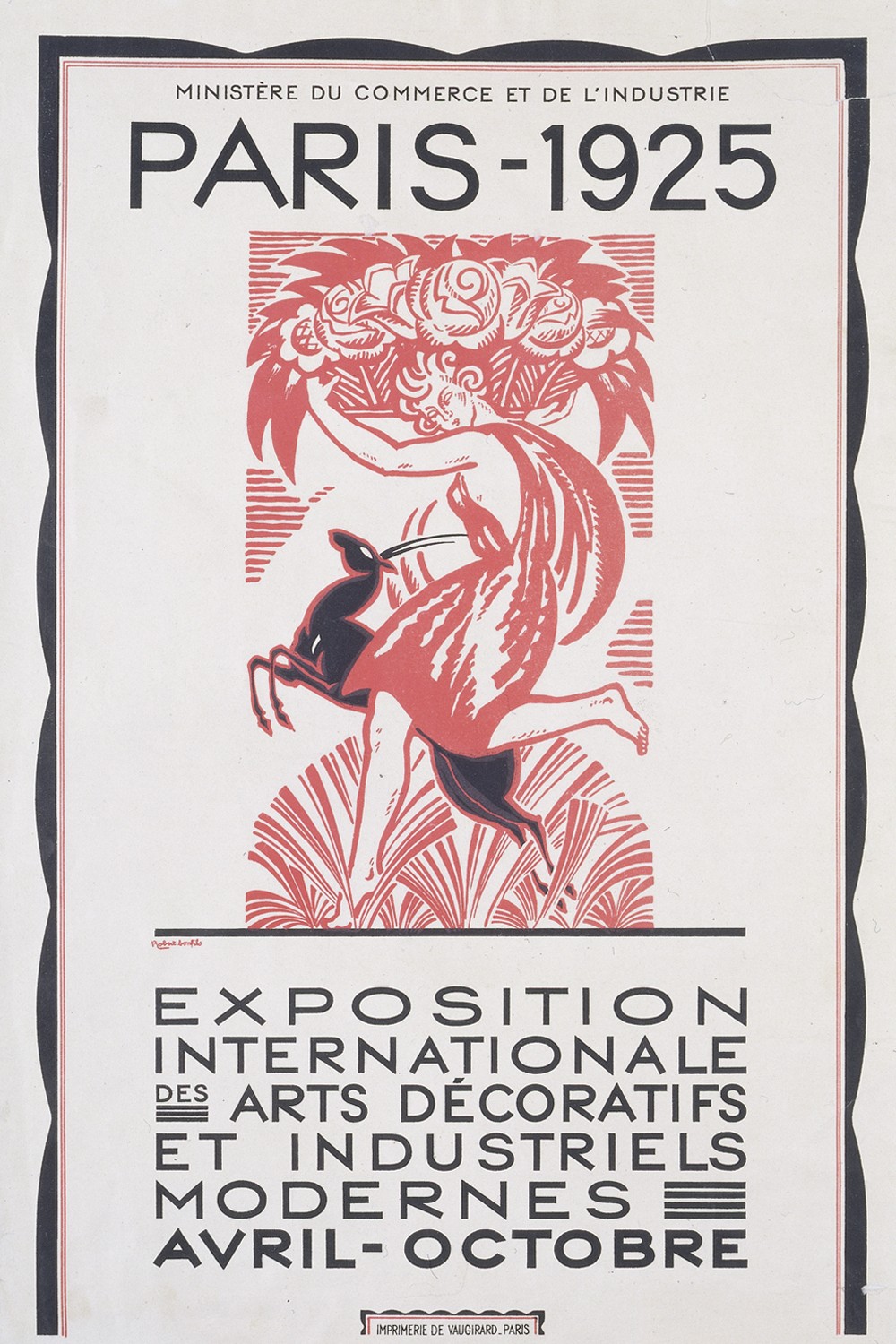

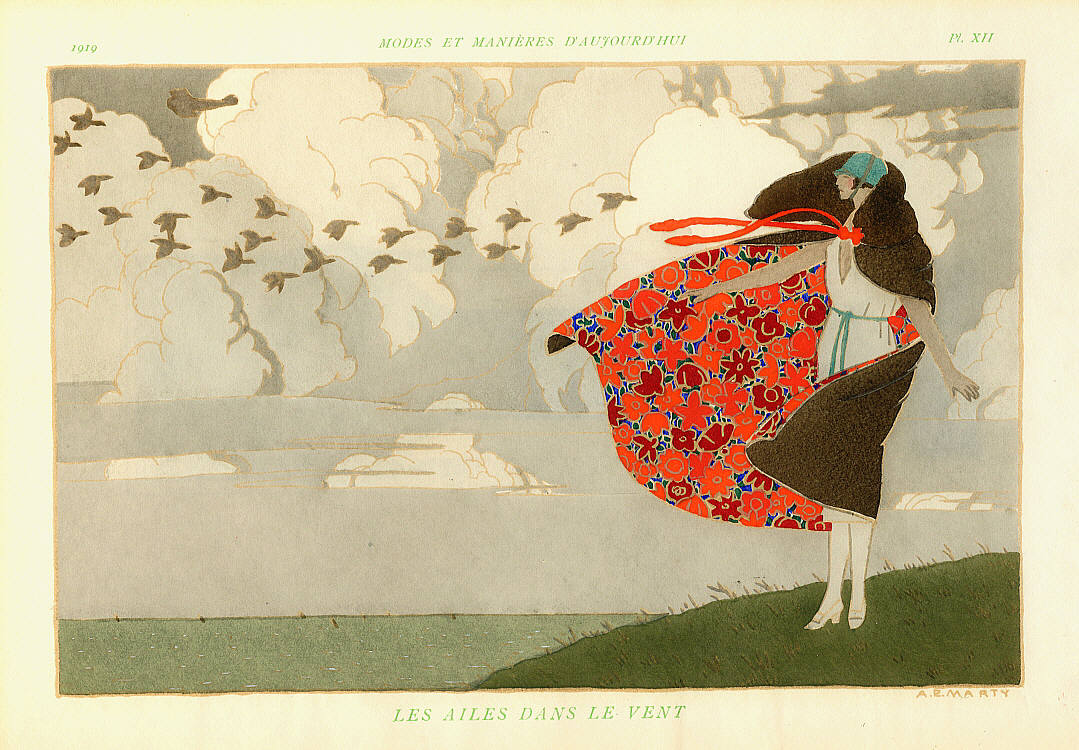

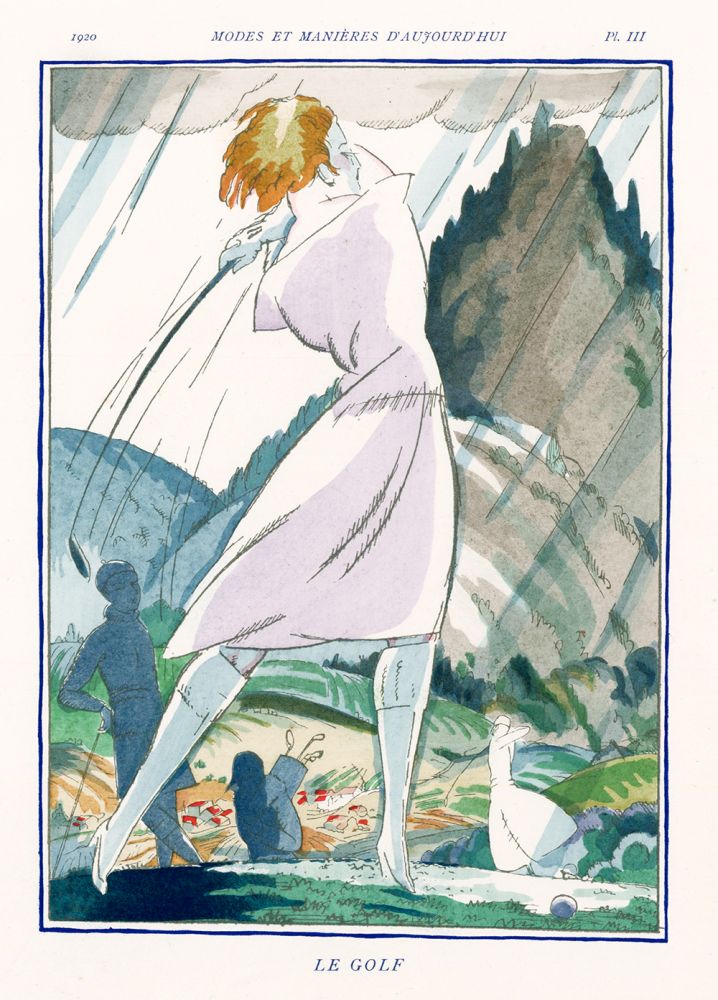

La moda del libro illustrato esplode nel decennio 1920-1930 in pieno periodo decò, nascono le prime forme di quello che sarà in seguito definito “libro d’arte”, si utilizzano carte preziose e raffinate e si studiano nuove tecniche d’illustrazione. Ritorna l’uso della tecnica del pochoir ovvero colorare a mano, mediante l’uso di mascherine di cartone, stampe il cui contorno è ottenuto mediante l’impressione di una lastra di zinco o di rame.

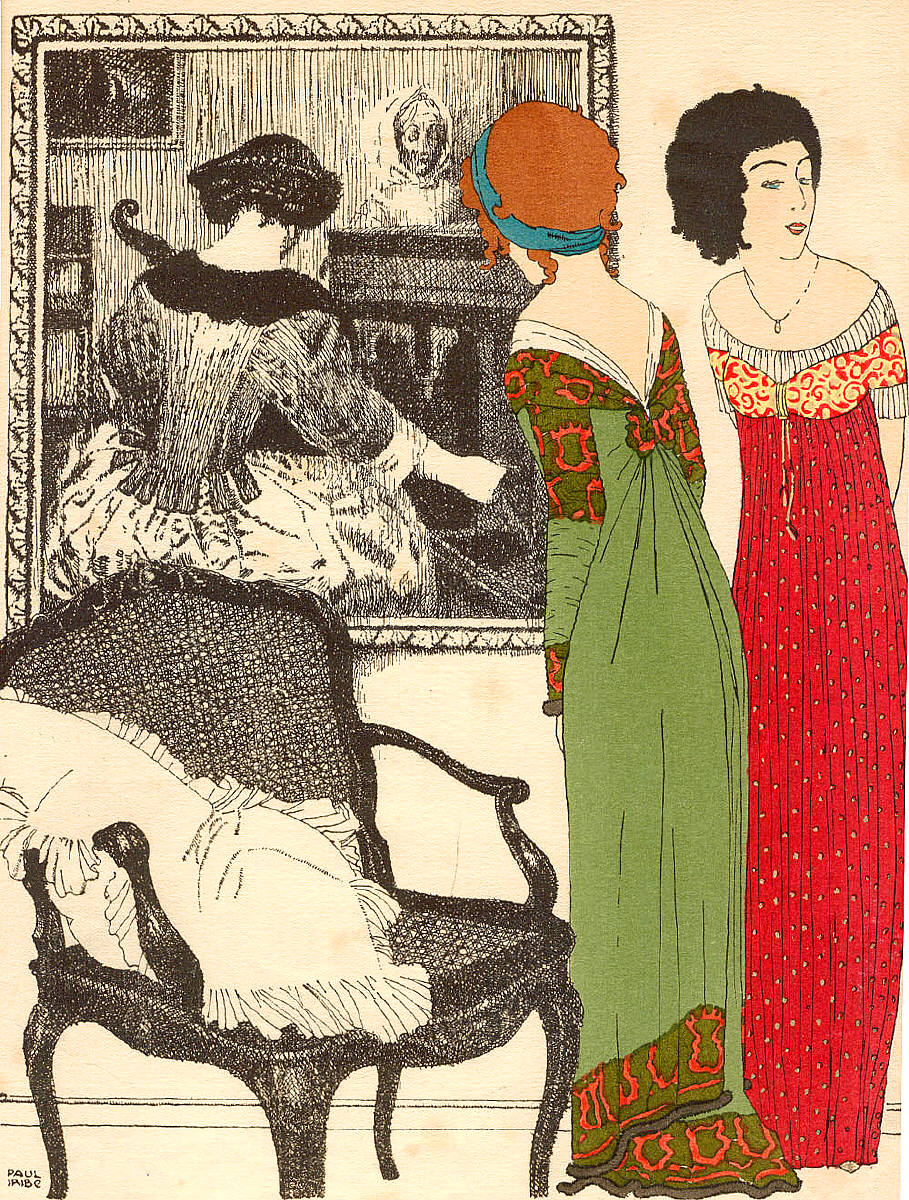

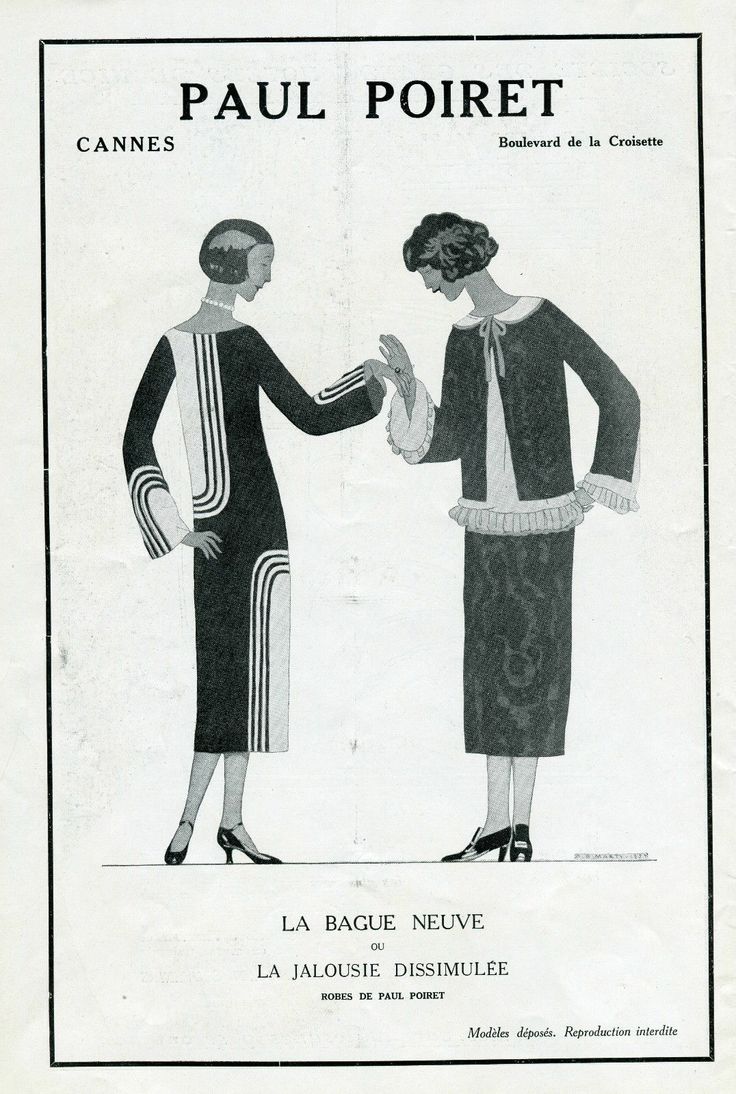

Paul Poiret è una delle figure più emblematiche nel mondo della moda di quel periodo, colui che ha inventato graficamente lo stile decò. Considerato il primo creatore di moda dei tempi moderni, ha avuto il merito di inserire la moda nell’arte e nel commercio. Influenzato dai movimenti artistici innovatori della Wiener Werkstette di Vienna e della Arts and Crafts inglese, fonda a Parigi l’Atelier Martine (1912-1929). Una vera e propria fucina di nuove idee nella moda e nei tessuti, nonché una grande scuola di design nella quale si succedono importanti pittori come Duffy, Iribe, Lepape e poi Erté, Bonfils, Zamora e Marty che daranno vita con le loro opere a periodici come la Gazette du Bon Ton che, insieme al Journal des Dames et de Modes, rappresenterà il massimo portavoce dell’eleganza e del gusto francese.

The 20th century, universally considered the period of great illustrators, is also defined as the golden age of illustration.

To understand its importance, we need to take a step back to when the Futurist manifesto by Italian poet and playwright Tommaso Marinetti was published in the French newspaper Figaro on February 20, 1909. This manifesto marked the formal and public beginning of this new era. It celebrated industrial civilization, exalting the theme of the modern metropolis as a hub of accelerated and frenetic life, rich in sensory and intellectual stimuli. It was a true declaration of war against traditional and classical culture. The founding fathers of this new artistic vision were Boccioni, Carrà, Russo, and Severini.

Following this wave, many artists realized the importance of artistic involvement in productive sectors in order to spread a certain way of writing and painting without the fear of compromising by also working for advertising.

This realization led to the expansion of artistic canons into popular areas such as fashion, interior design, and advertising.

FASHION AND MAGAZINES

A particularly prominent sector during this period is represented by the decoration of books and magazines.

Illustrated books as well as magazines and newspapers quickly became important platforms for painters and young artists.

The trend of illustrated books exploded in the 1920s-1930s during the full Art Deco period. The first forms of what would later be termed “art books” emerged, using precious and refined papers and studying new illustration techniques. The technique of pochoir, which involves hand-coloring through the use of cardboard stencils, re-emerged. Prints were created by imprinting the outline from a zinc or copper plate.

Paul Poiret stands as one of the most emblematic figures in the fashion world of that period, credited with graphically inventing the Art Deco style. Regarded as the first modern fashion designer, he succeeded in merging fashion with art and commerce. Influenced by innovative artistic movements like the Vienna Secession of the Wiener Werkstätte and English Arts and Crafts, he founded the Atelier Martine in Paris (1912-1929). It became a true source of new ideas in fashion and textiles, as well as a major design school where significant painters like Duffy, Iribe, Lepape, and later Erté, Bonfils, Zamora, and Marty succeeded one another. Through their works, they gave life to periodicals like the Gazette du Bon Ton, which, along with the Journal des Dames et de Modes, became the leading voices of French elegance and taste.

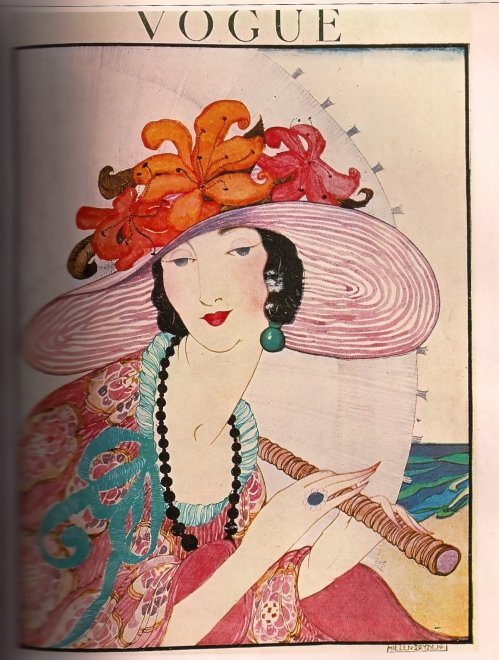

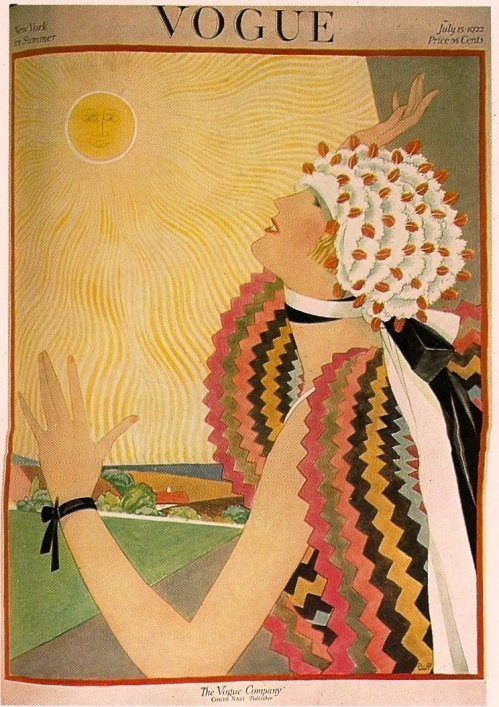

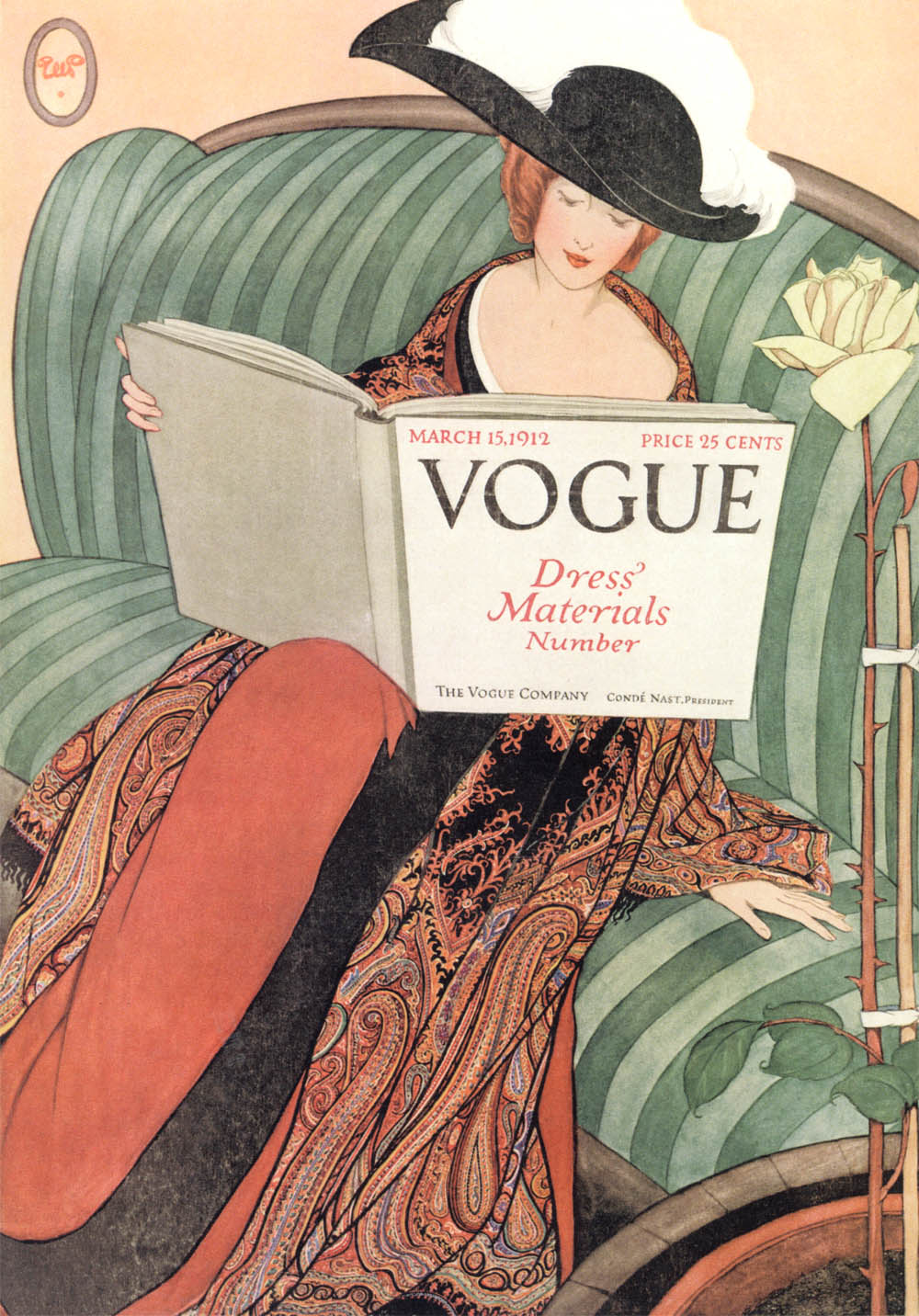

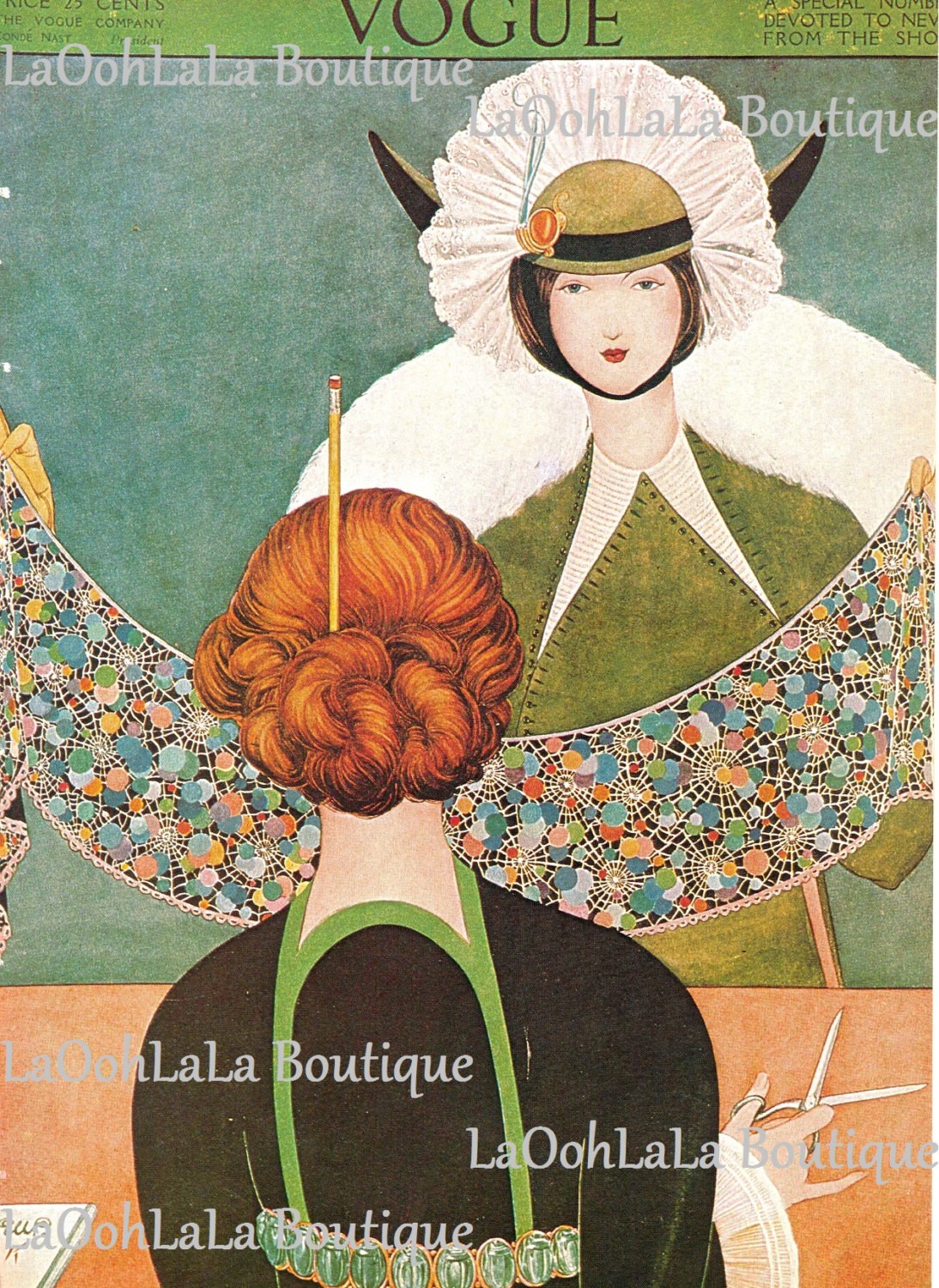

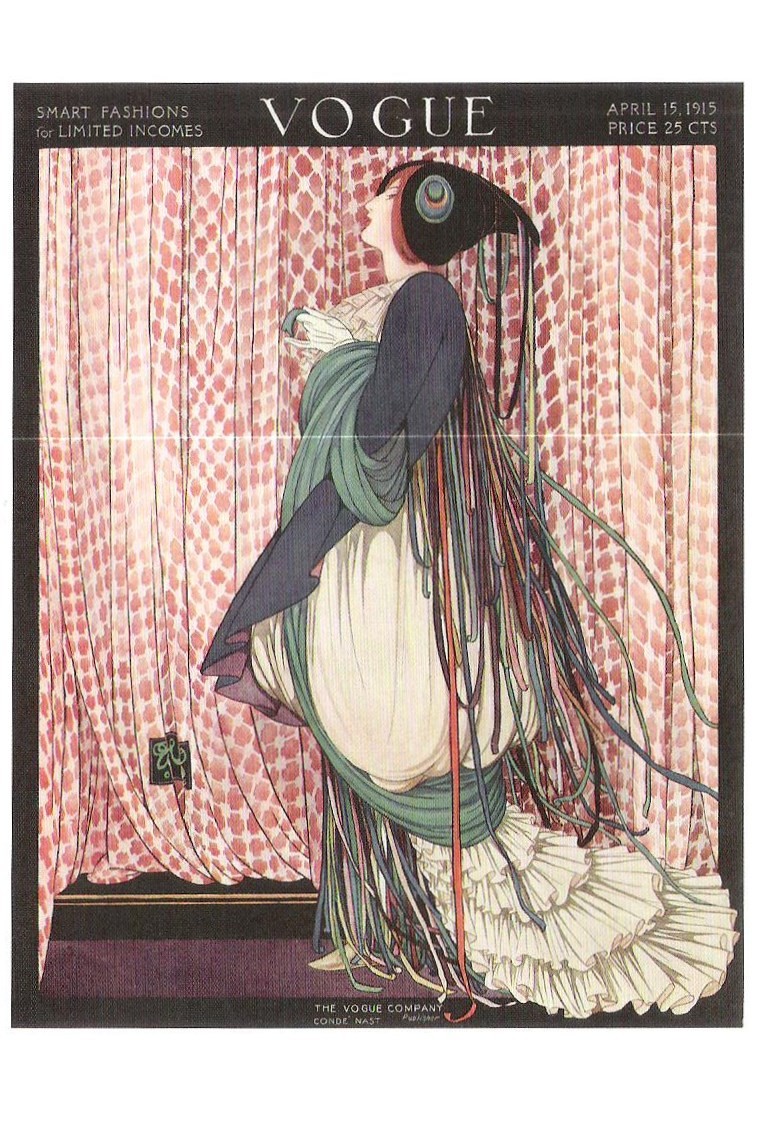

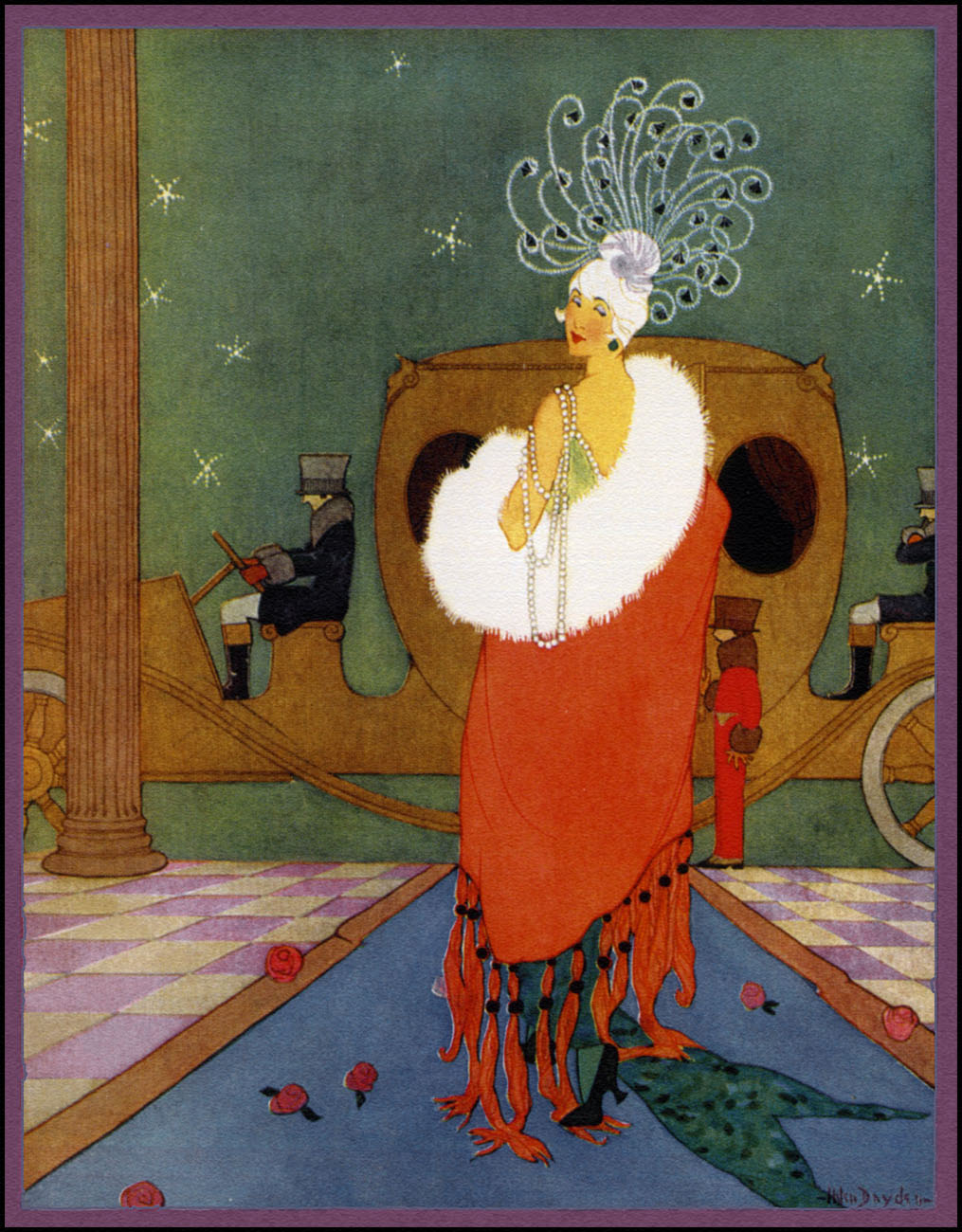

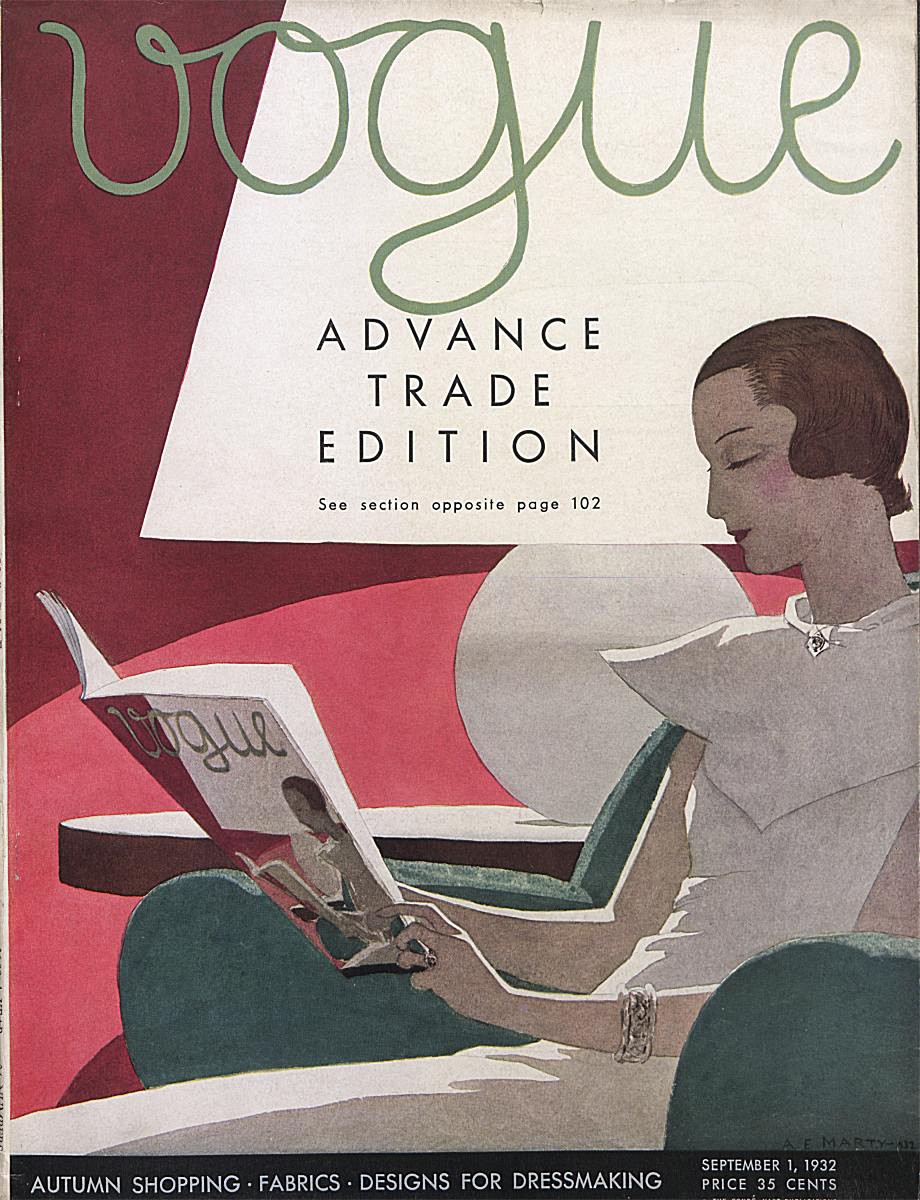

Questa moda ha risonanza mondiale al punto che anche Vogue, la rivista statunitense fondata da Arthur Turnure nel 1892 e acquistata da Condé William Nast nel 1909, negli anni venti si avvale per la sua pubblicità di due importantissimi illustratori americani, George Wolfe Plank (1883-1965) e Helen Dryden (1887-1981).

This fashion had a worldwide impact to the extent that even Vogue, the American magazine founded by Arthur Turnure in 1892 and acquired by Condé William Nast in 1909, employed two highly significant American illustrators for its advertising in the 1920s: George Wolfe Plank (1883-1965) and Helen Dryden (1887-1981).

Helen Dryden 1919 per Vogue Stati Uniti

George Wolfe Plank 1922 per Vogue Stati Uniti

George Wolfe Plank per Vogue Stati Uniti

George Wolfe Plank per Vogue Stati Uniti

George Wolfe Plank 1917 per Vogue Stati Uniti

George Plank 1915 Vogue

Helen Dryden - Vogue

Helen Dryden - Vogue

Marty - Vogue 1932

Couple in evening wear emerging from revolving door - George Lepape 1933

L’ILLUSTRAZIONE E LA PUBBLICITA’

Inizialmente la pubblicità era molto semplice e immediata, realizzata soprattutto tramite disegni dato che la maggior parte della popolazione era analfabeta e solo pochi sapevano e potevano leggere i manifesti e i giornali.

In Italia la comunicazione si sviluppa particolarmente attraverso le ultime pagine dei quotidiani, dei settimanali o di riviste come la Domenica del Corriere, la Tribuna Illustrata e l’ Illustrazione Italiana, dove appaiono i primi comunicati pubblicitari nei quali, oltre alle mirabili illustrazioni, s’iniziano a intravedere le prime ricerche per lo studio di nuovi caratteri di stampa.

Gli illustratori europei più rappresentativi

Uno dei pionieri della cartellonistica e dell’illustrazione pubblicitaria italiana fu il pittore futurista Giorgio Muggiani (1887-1938); egli fu tra gli iniziatori di questa nuova forma d’arte pubblicitaria italiana insieme a Marcello Dudovich, Fortunato Depero, Leonetto Cappiello, Leopoldo Metlicovitz, Arturo Panni, Jean D’Ylean, Enrico Sacchetti, Marcello Nizzoli e altri. Nel 1914 Muggiani disegnò la testata del giornale Il Popolo d’Italia, modello grafico al quale si sarebbe poi uniformata la gran parte delle altre testate giornalistiche.

ILLUSTRATION AND ADVERTISING

Initially, advertising was simple and direct, primarily executed through illustrations, as a significant portion of the population was illiterate, and only a few could read posters and newspapers.

In Italy, communication particularly evolved through the final pages of newspapers, weeklies, or magazines such as “Domenica del Corriere,” “Tribuna Illustrata,” and “Illustrazione Italiana.” These were the platforms where the first advertising announcements appeared, featuring remarkable illustrations and providing glimpses into the initial explorations of new typefaces.

The most prominent European illustrators

One of the pioneers of poster art and Italian advertising illustration was the Futurist painter Giorgio Muggiani (1887-1938). He was among the initiators of this new form of Italian advertising art alongside Marcello Dudovich, Fortunato Depero, Leonetto Cappiello, Leopoldo Metlicovitz, Arturo Panni, Jean D’Ylen, Enrico Sacchetti, Marcello Nizzoli, and others. In 1914, Muggiani designed the masthead of the newspaper “Il Popolo d’Italia,” a graphic template that would later be adopted by a majority of other journalistic publications.

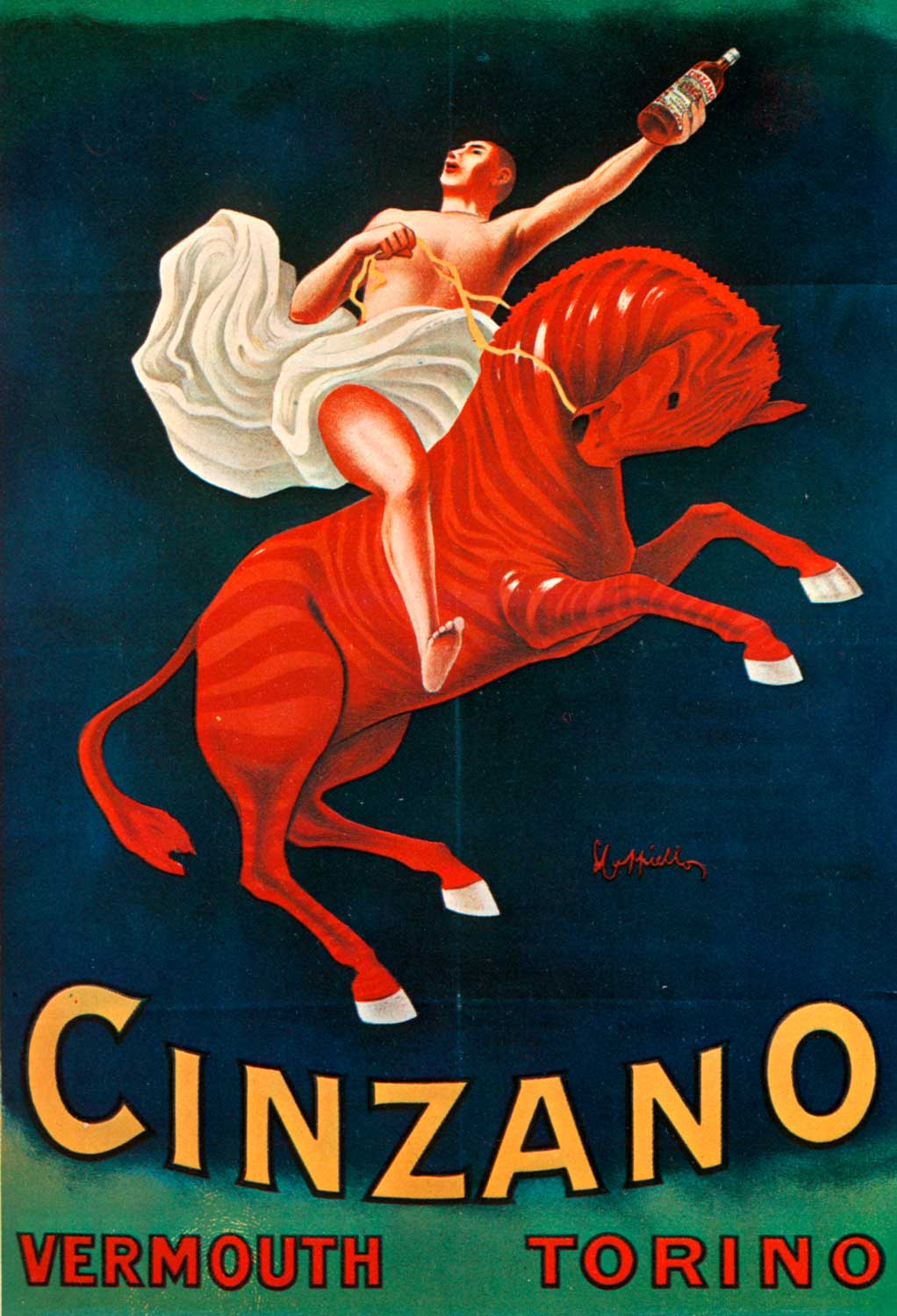

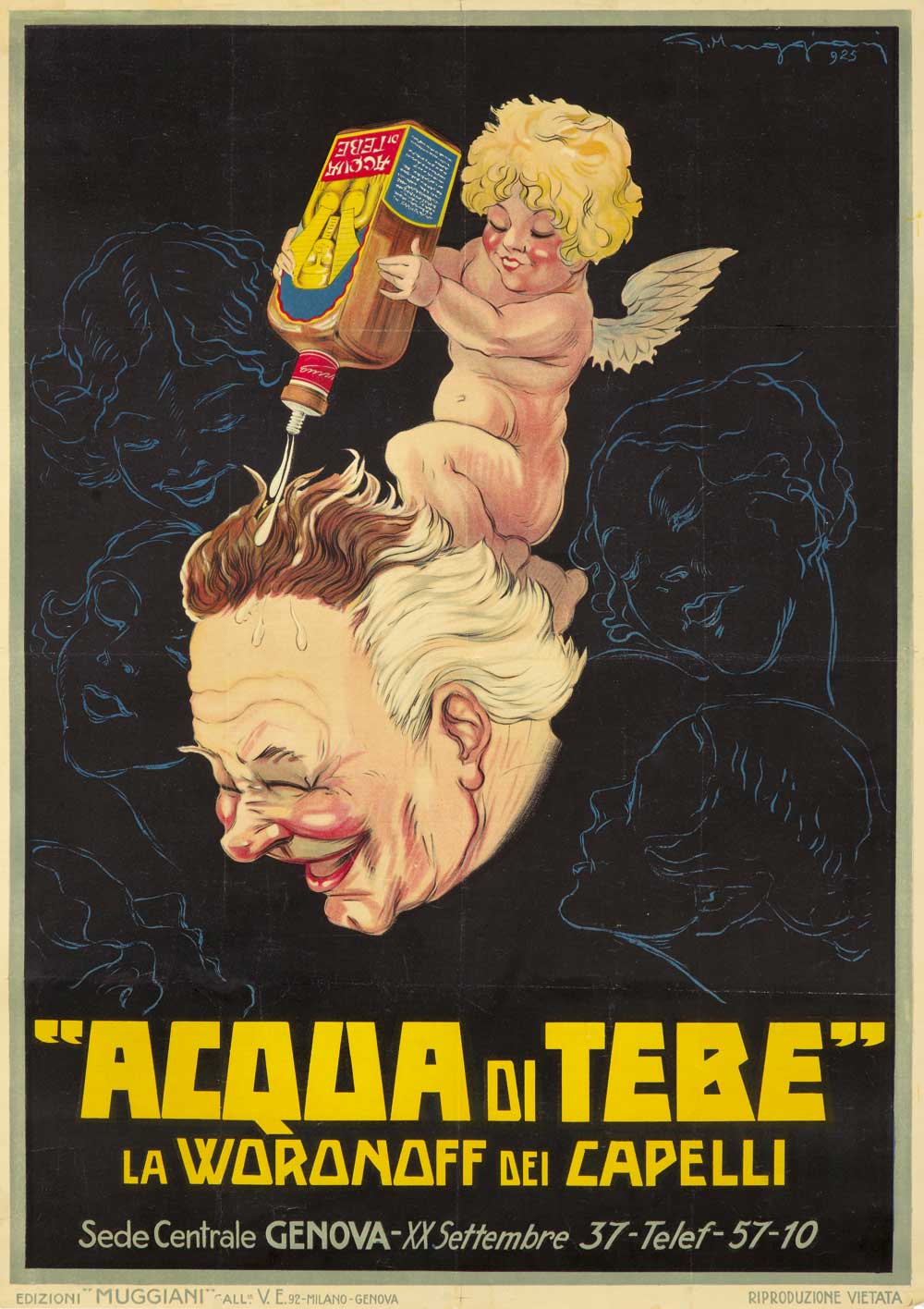

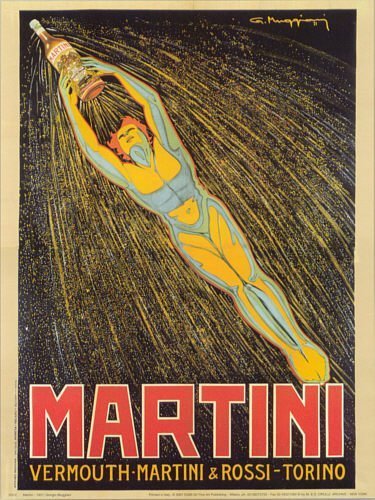

Le “campagne” promozionali di Cinzano, Pirelli, Società di Navigazione, Rinascente, Lana Gatto, Martini (1921), Biscotti Lazzaroni (1928), Moto Guzzi (1917), Borsalino, Florio, Recoaro e Hair Coloring Tonic (Acqua di Tebe) sono solo alcuni dei suoi lavori più famosi.

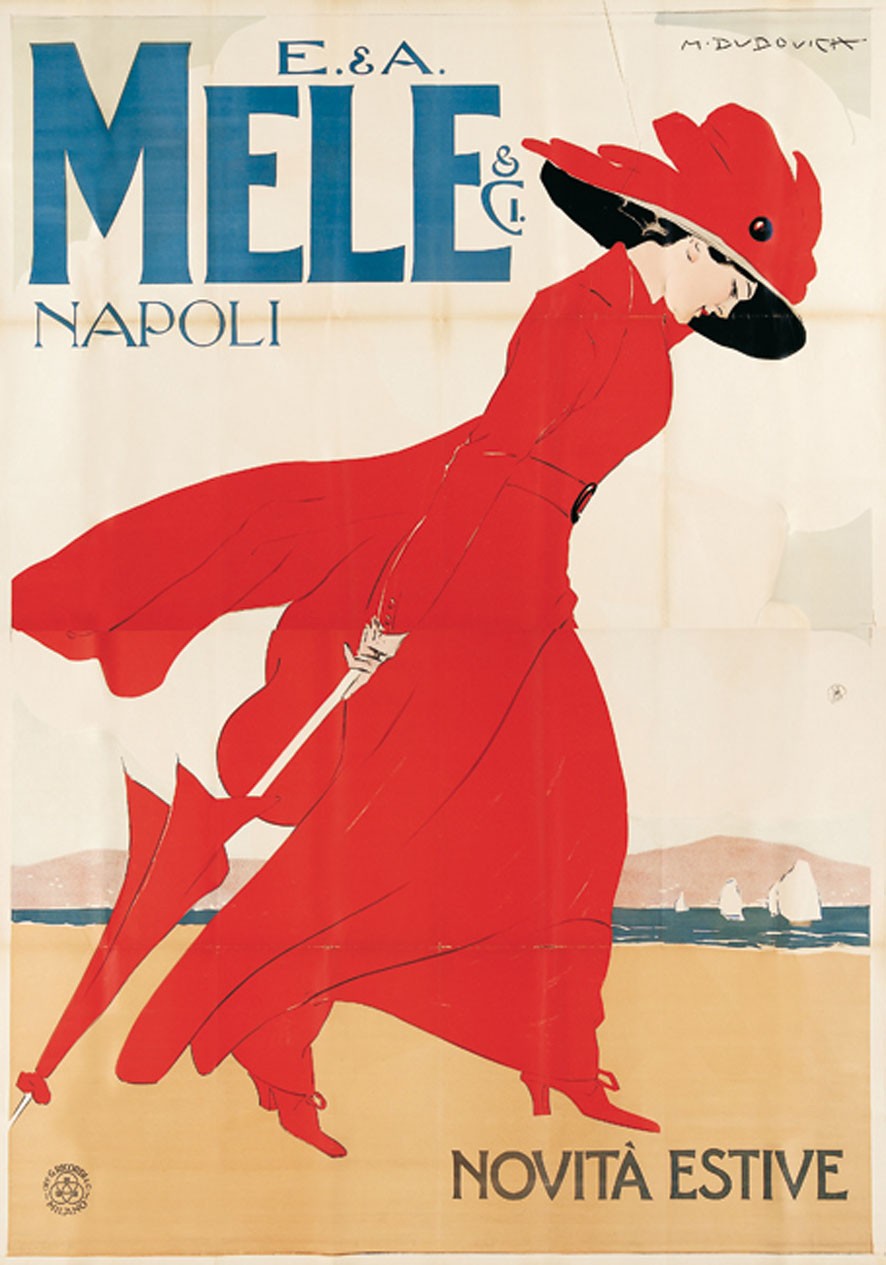

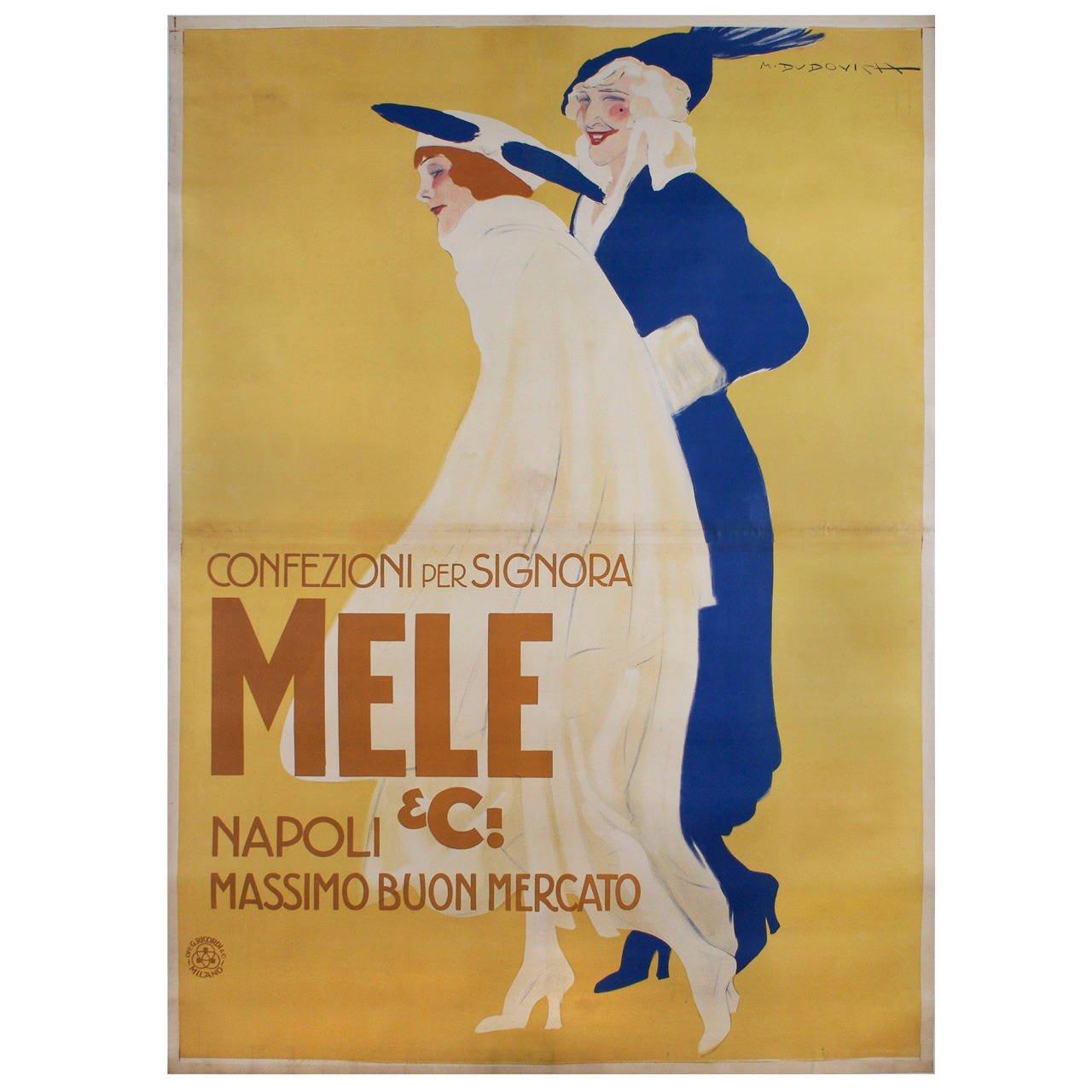

Marcello Dudovich (1878-1962), istriano, lo si può benissimo definire uno dei massimi esponenti della grafica italiana, per quasi cinquant’anni non ci fu grande industria italiana che non fece ricorso alla sua genialità nell’inventare ed eseguire gli splendidi cartelloni commissionatogli. Fu anche uno dei più prolifici, disegnò infatti circa 396 manifesti, conservati presso la civica Raccolta Bertarelli al Castello Sforzesco di Milano, la Raccolta Salce del museo Bailo di Treviso, l’archivio Rinascente e l’archivio Ricordi di Milano.

The promotional “campaigns” of Cinzano, Pirelli, Società di Navigazione, Rinascente, Lana Gatto, Martini (1921), Biscotti Lazzaroni (1928), Moto Guzzi (1917), Borsalino, Florio, Recoaro, and Hair Coloring Tonic (Acqua di Tebe) are just a few of his most famous works.

Marcello Dudovich (1878-1962), originally from Istria, can certainly be regarded as one of the foremost figures in Italian graphic design. For nearly fifty years, there was hardly any significant Italian industry that did not rely on his genius to conceive and execute splendid commissioned posters. He was also one of the most prolific, having designed around 396 posters. These works are preserved in the Civica Raccolta Bertarelli at the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, the Raccolta Salce at the Bailo Museum in Treviso, the Rinascente archives, and the Ricordi archives in Milan.

Marcello Dudovich: Pubblicità Martini & Rossi 1921

Marcello Dudovich : Pubblicità Rinascente anni ‘20

Dudovich Rinascente 1920

Dudovich - Mele

Dudovich - Mele

Dudovich Afga

Dudovich Pirelli

Leonetto Cappiello

Giorgo Muggiani

Muggiani - Lazzaroni 1928

Giorgio Muggiani: Pubblicità Martini 1921

Muggiani

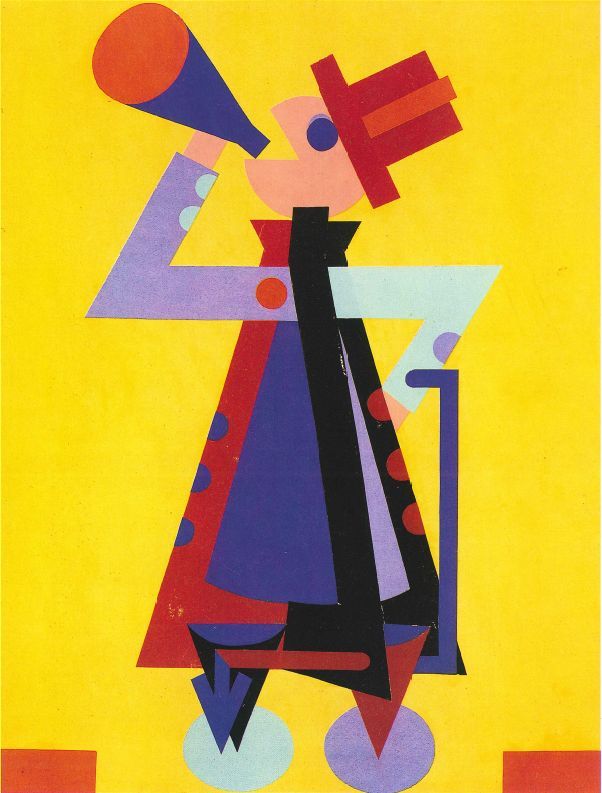

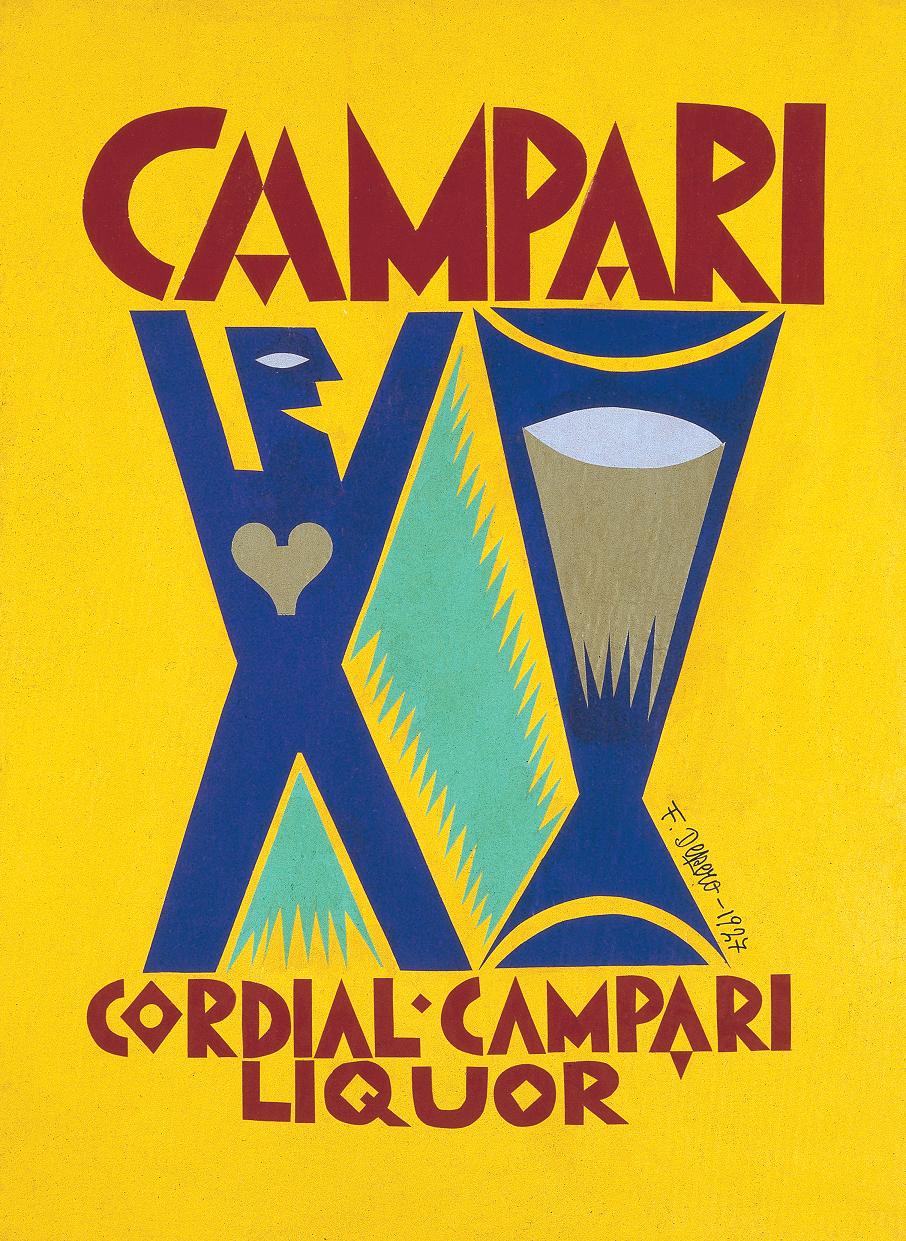

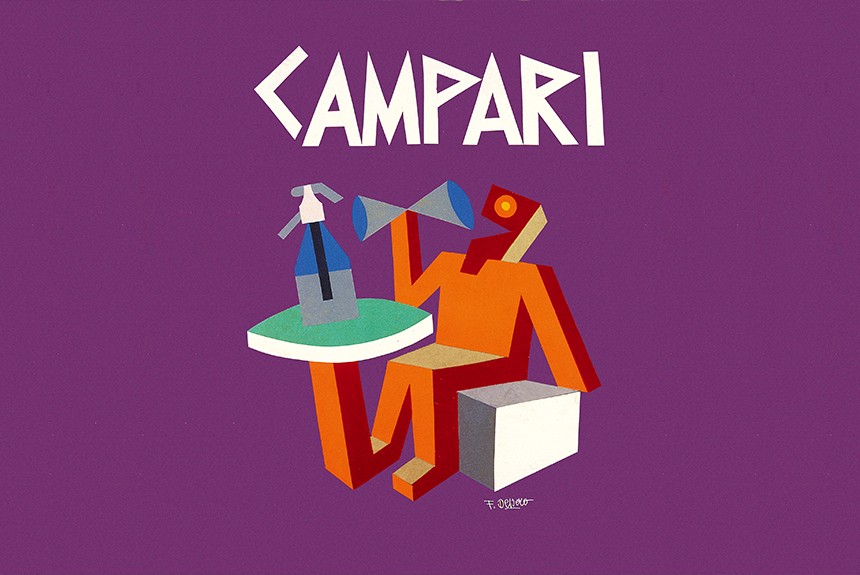

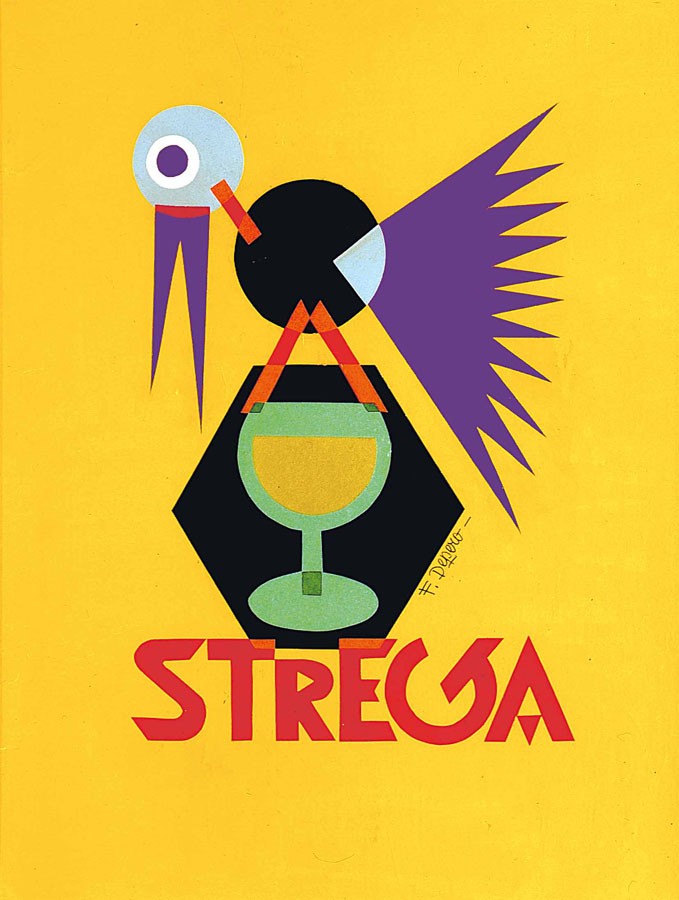

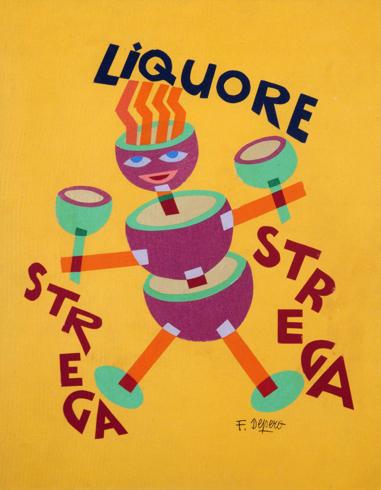

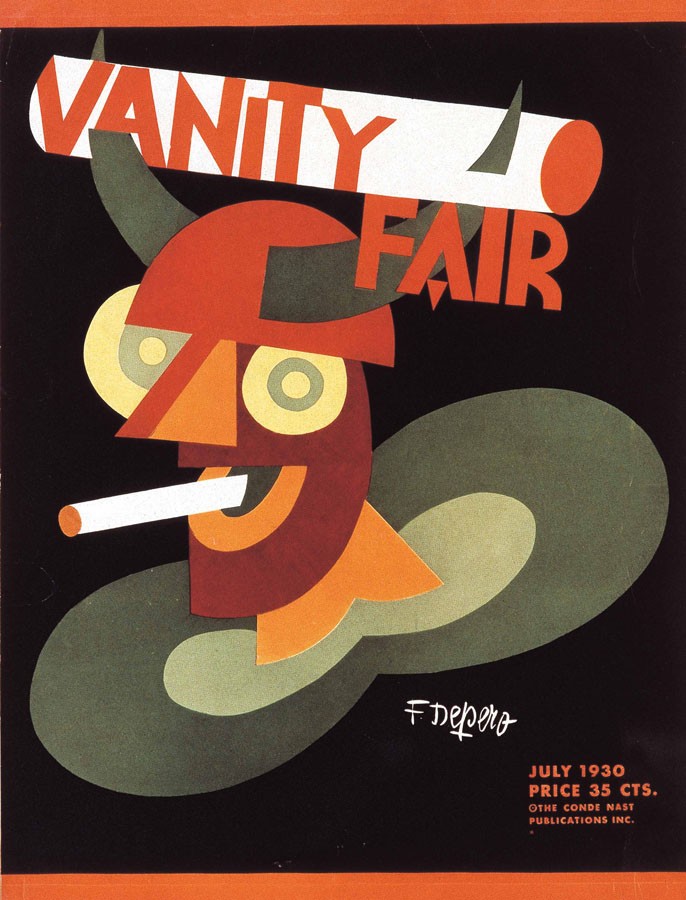

Parlare dell’italiano Fortunato Depero (1892-1960) è sempre molto riduttivo, promotore del movimento Futurista e artista a 360 gradi, ha con la Campari un lungo sodalizio, sua è la progettazione nel 1932 per Camparisoda della famosa bottiglia a forma di calice rovesciato su suggerimento dello stesso Davide Campari, come pure con la società Alberti, produttrice del liquore Strega e per la Schering con la pubblicità del Veramon. In brevissimo tempo Depero diventerà il più autorevole cartellonista pubblicitario tra i Futuristi.

Talking about the Italian artist Fortunato Depero (1892-1960) is always quite limiting. A promoter of the Futurist movement and a versatile artist, his association with Campari is significant. He was responsible for the design, in 1932, of the iconic bottle for Camparisoda, shaped like an inverted glass, on the suggestion of Davide Campari himself. Depero also collaborated with the Alberti company, producer of Strega liqueur, and worked on advertising for Schering’s Veramon.

In a very short time, Depero became the most authoritative advertising poster artist among the Futurists. His contributions went beyond just illustration, as he was a true innovator in design and played a significant role in shaping the aesthetics of advertising during that era.

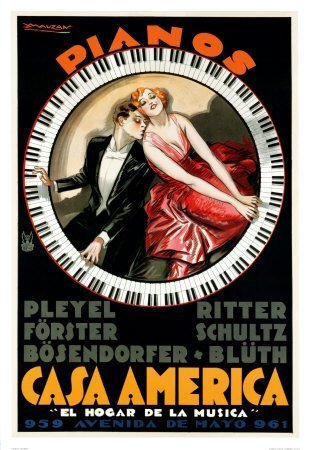

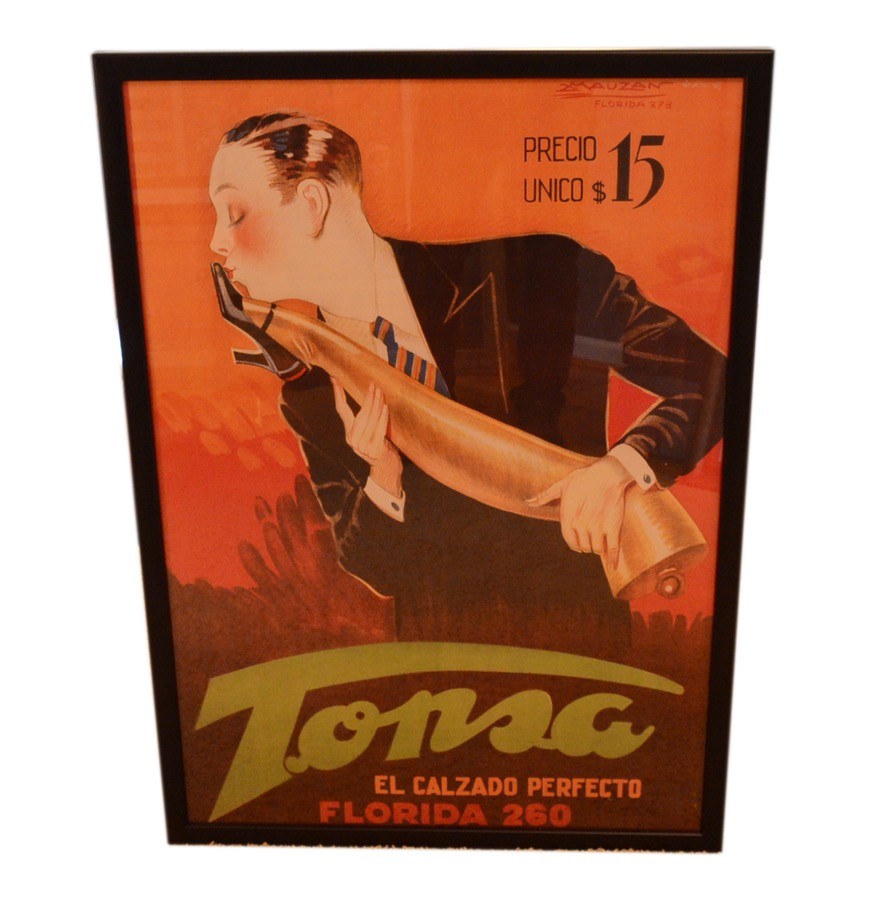

Il francese Achille Luciano Mauzan (1883-1952) ha al suo attivo circa 1500 locandine di film, prodotte tra il 1909 e il 1913, nonché un numero enorme di cartelloni pubblicitari per società francesi, argentine e italiane.

The French artist Achille Luciano Mauzan (1883-1952) created around 1500 movie posters, produced between 1909 and 1913, in addition to an extensive number of advertising posters for French, Argentine, and Italian companies. Mauzan’s prolific output in both movie and advertising posters showcases his versatility and impact on visual communication during that period.

Lo spagnolo Maximo Ramos (1880-1944) lavora con diverse riviste dell’epoca, inizialmente con Correo Gallego, fondato nel 1878 e divenuto il quotidiano più importante di Santiago di Compostela in Galizia. Ramos diventa uno dei maggiori illustratori ed incisori dell’epoca e il suo stile riflette le influenze della corrente inglese coeva dell’Arts and Craft inglese nonché quella della stampa giapponese allora in voga in Europa per le raffigurazioni femminili. Dopo aver lavorato negli Stati Uniti, Messico, Cuba e Argentina, torna in Spagna collaborando come pubblicitario e illustratore con le più importanti riviste: Blanco y Negro, La Esfera, El Nuevo Mundo.

The Spanish artist Maximo Ramos (1880-1944) worked with various magazines of his time, starting with Correo Gallego, founded in 1878, which became the most important newspaper in Santiago de Compostela, Galicia. Ramos emerged as one of the leading illustrators and engravers of his era, and his style reflects influences from the concurrent English Arts and Crafts movement, as well as the Japanese printmaking trend popular in Europe for depictions of women. After working in the United States, Mexico, Cuba, and Argentina, he returned to Spain and collaborated as both an advertising artist and illustrator with prominent magazines such as Blanco y Negro, La Esfera, and El Nuevo Mundo.

Narciso Méndez Bringa (1868-1933) spagnolo, deve la sua popolarità alle illustrazioni che realizza per le fiabe di Christian Andersen rendendo famosi e particolarmente apprezzati in Spagna questi racconti. A seguito di questo successo inizia una proficua collaborazione con l’editore Calleja, per la rivista La Ilustración Española y Americana e per Blanco y Negro nella quale illustra novelle e racconti.

Narciso Méndez Bringa (1868-1933), a Spanish artist, owes his popularity to the illustrations he created for the fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen, making these stories well-known and highly appreciated in Spain. Following this success, he embarked on a fruitful collaboration with the publisher Calleja, contributing to the magazine “La Ilustración Española y Americana” and “Blanco y Negro,” where he illustrated short stories and narratives. His artistic contributions significantly enriched the visual storytelling landscape in Spain during that period.

Non ultimo per importanza, tra gli spagnoli è Ramòn Casas (1866-1932), oltre che pittore famoso per i suoi ritratti e caricature dell’alta società di Barcellona, è anche disegnatore grafico e cartellonista pubblicitario e diffonde ampiamente il movimento modernista.

Last but not least among the Spanish artists is Ramón Casas (1866-1932). Apart from being a renowned painter known for his portraits and caricatures of Barcelona’s high society, he was also a graphic designer and advertising poster artist who played a significant role in spreading the modernist movement. His multifaceted contributions extended from fine art to graphic design, and his work had a profound influence on the visual culture of the time, especially within the context of modernism.

La pubblicità, sia come illustrazione grafica che cartellonistica, riesce quindi ad entrare nelle case ed arredare il paesaggio urbano con delicatezza, mostrando spesso anche i tratti e le curve disegnate di giovani donne sorridenti e ingenuamente ammiccanti, con la leggera ipocrisia di quell’epoca ma sicuramente con tanta grazia e buon gusto.

Advertising, both in graphic illustration and poster art, managed to enter homes and adorn the urban landscape with a delicate touch. It often showcased the contours and curves of young women, portrayed with smiles and innocent flirtation. While reflecting the slight hypocrisy of that era, this advertising undoubtedly exuded grace and refined taste, capturing the essence of the time with its unique charm.

©Giusy Baffi 2020 – pubblicato su Cose Belle Antiche&Moderne marzo 2011 e su artevitae.it il 27 marzo 2017

© Le foto sono state reperite da libri e cataloghi d’asta o in rete e possono essere soggette a copyright. L’uso delle immagini e dei video sono esclusivamente a scopo esplicativo. L’intento di questo blog è solo didattico e informativo. Qualora la pubblicazione delle immagini violasse eventuali diritti d’autore si prega di volerlo comunicare via email a info@giusybaffi.com e saranno prontamente rimosse oppure citato il copyright ©.

© Il presente sito https://giusybaffi.com/ non è a scopo di lucro e qualsiasi sfruttamento, riproduzione, duplicazione, copiatura o distribuzione dei Contenuti del Sito per fini commerciali è vietata.

© The photos have been sourced from books, auction catalogs, or online and may be subject to copyright. The use of images and videos is solely for explanatory purposes. The intent of this blog is purely educational and informational. If the publication of images were to violate any copyright, please communicate this via email to info@giusybaffi.com, and they will be promptly removed or the copyright © will be cited.

© The present website https://giusybaffi.com/ is not for profit, and any exploitation, reproduction, duplication, copying, or distribution of the Site’s Content for commercial purposes is prohibited.