IL MICROMOSAICO E IL GRAND TOUR, PREZIOSE CARTOLINE DALL’ITALIA – The micro-mosaic and the Grand Tour, precious postcards from Italy-

GLI ESORDI

Fin dai tempi più antichi l’Italia vanta una lunga tradizione nell’arte musiva: dai mosaici dell’antica Roma, passando a quelli bizantini che hanno in Ravenna una delle due città imperiali (l’altra era Costantinopoli) esaltandosi nella Sicilia di epoca normanna con la Cappella Palatina, attraversando il virtuosismo musivo di San Marco a Venezia per poi tornare a primeggiare a Roma nel 1700.

E’ infatti a Roma che nel 1727 viene istituito lo Studio Vaticano del Mosaico con un gran numero di mosaicisti alle dipendenze della Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro.

LA SCOPERTA

Nel 1731 Alessio Mattioli, fabbricante di paste vitree, scopre una formula a base di stucco e olio di lino che permetteva, filando gli smalti in bacchette, di preparare tessere di misura estremamente ridotta , anche inferiore al millimetro e con una vastissima gamma di colorazioni, si parla di oltre 18.000 tonalità di colore.

E’ l’inizio del micromosaico.

THE BEGINNINGS

Since ancient times, Italy boasts a long tradition in mosaic art: from the mosaics of ancient Rome, passing through the Byzantine ones, with Ravenna being one of the two imperial cities (the other was Constantinople), reaching its peak in Norman Sicily with the Palatine Chapel. It then continues through the mosaic virtuosity of San Marco in Venice before returning to prominence in Rome in the 1700s.

Indeed, it is in Rome that the Vatican Mosaic Studio is established in 1727, with a large number of mosaic artists under the authority of the Reverend Fabric of St. Peter.

THE DISCOVERY

In 1731, Alessio Mattioli, a manufacturer of vitreous pastes, discovers a formula based on plaster and linseed oil. This formula allows, by spinning the enamels into rods, the preparation of extremely small tesserae, even less than a millimeter, with an extensive range of colors—over 18,000 color tones.

This marks the beginning of micromosaic.

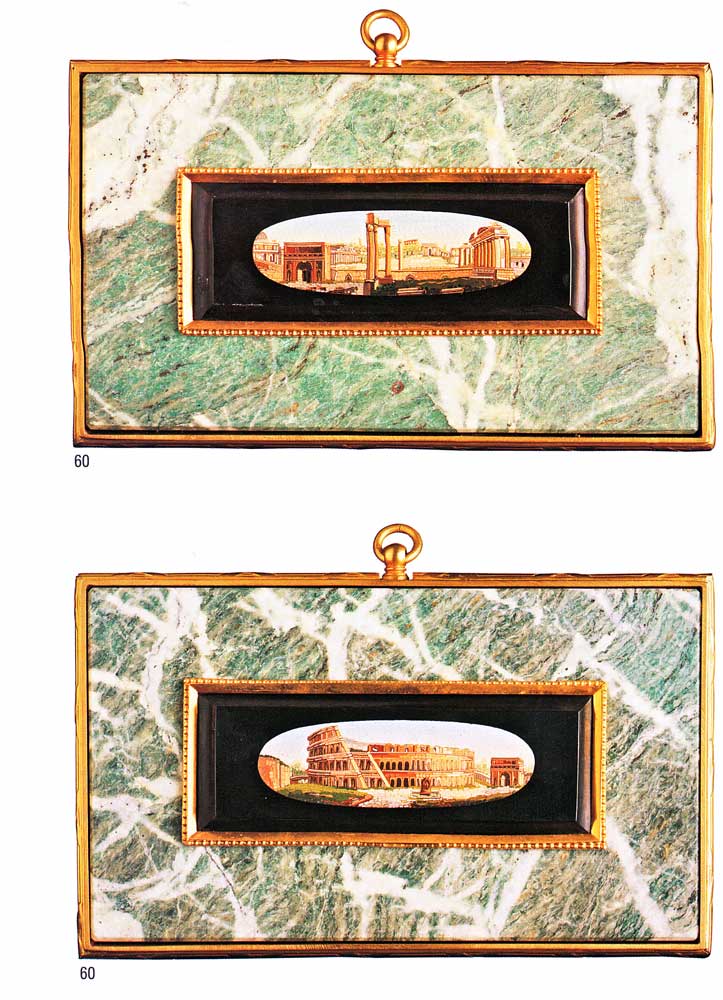

I PICCOLI PREZIOSI CAPOLAVORI

All’interno dello Studio Vaticano i lavori in micromosaico furono introdotti in un momento in cui mancava il lavoro ed i mosaicisti erano privi del necessario guadagno per vivere. Il successo del settore privato del micromosaico in questa prima fase si può far risalire alle seguenti circostanze: la cultura neoclassica.

Le opere in micromosaico applicate nella decorazione di oggetti personali e d’arredamento quali piani di tavolo, quadretti, tabacchiere e gioielli, divennero di gran moda.

THE SMALL PRECIOUS MASTERPIECES

Within the Vatican Mosaic Studio, micromosaic works were introduced at a time when there was a lack of employment, and mosaic artists lacked the necessary income to sustain themselves. The success of the private sector in micromosaic during this initial phase can be attributed to the following circumstances: the neoclassical culture.

Micromosaic works applied in the decoration of personal and home items, such as tabletops, small pictures, snuffboxes, and jewelry, became highly fashionable.

Questa produzione di lusso si diffuse presso papi, diplomatici e aristocratici; orefici e argentieri richiedevano placchette in micromosaico da applicare agli oggetti preziosi.

This luxury production spread among popes, diplomats, and aristocrats; goldsmiths and silversmiths sought micromosaic plaques to apply to precious objects.

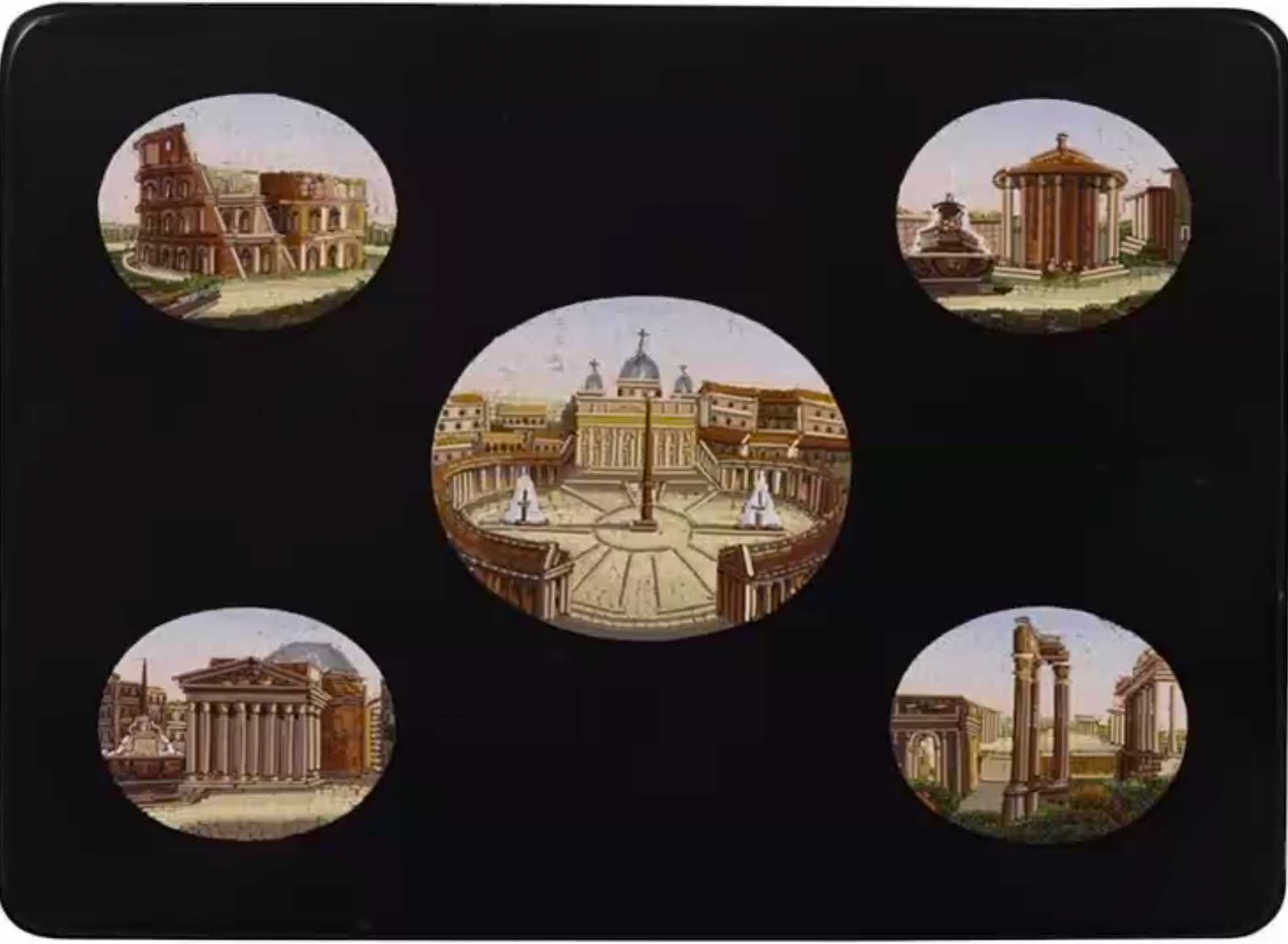

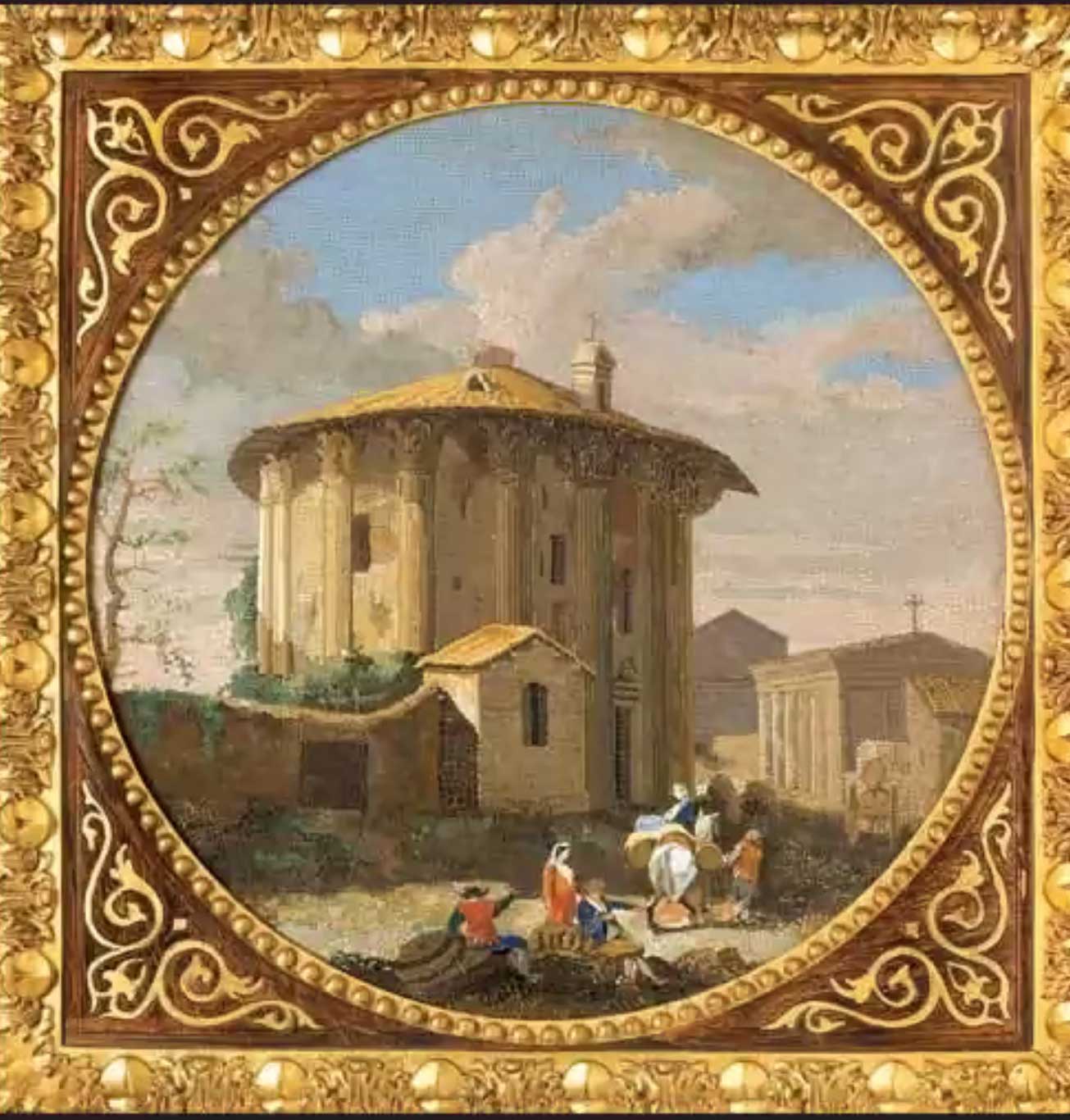

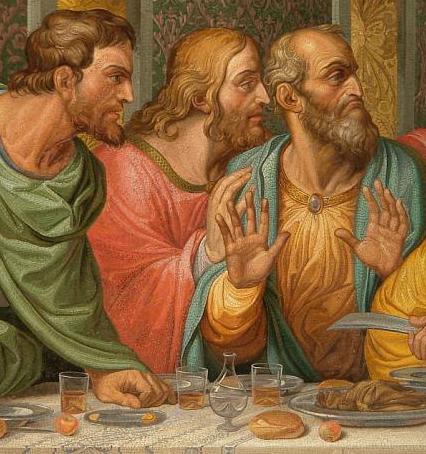

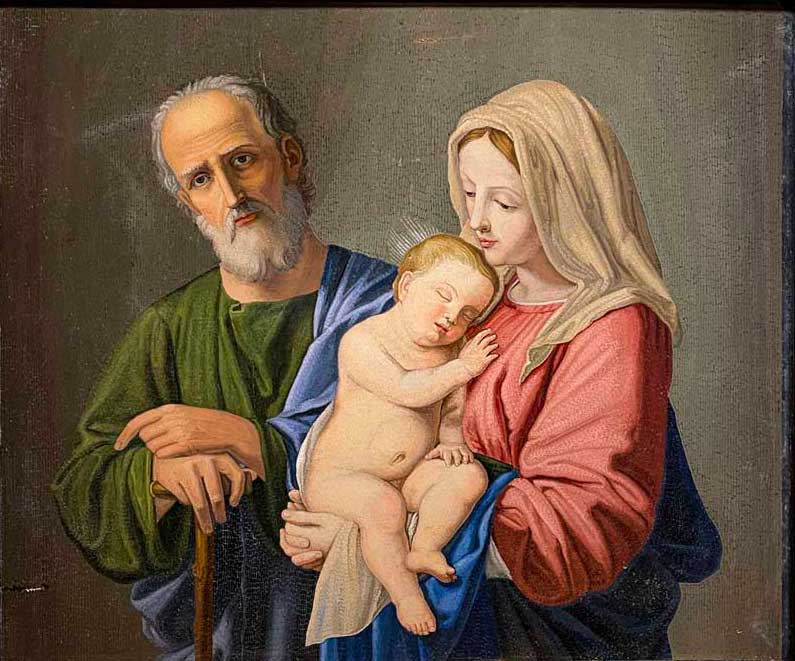

I SOGGETTI

I soggetti iconografici si richiamavano alle tematiche antiche tornate di gran moda con le nuove scoperte archeologiche, ai monumenti di Roma, alla campagna romana, a personaggi e scene tratte dal mito o dalle pitture antiche oltre che una vasta rappresentazione di animali, di composizioni floreali e personaggi.

THE SUBJECTS

The iconographic subjects referred to ancient themes that became highly fashionable with new archaeological discoveries, to the monuments of Rome, the Roman countryside, to characters and scenes from mythology or ancient paintings, as well as a broad representation of animals, floral compositions, and figures.

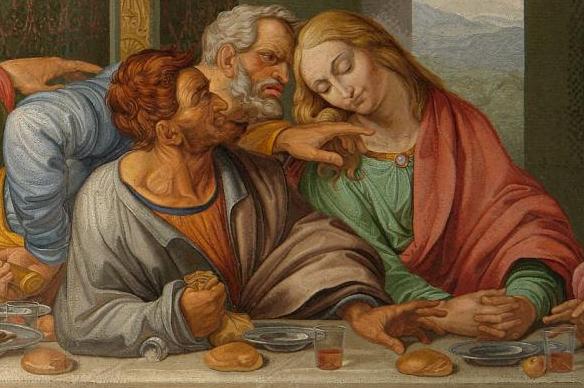

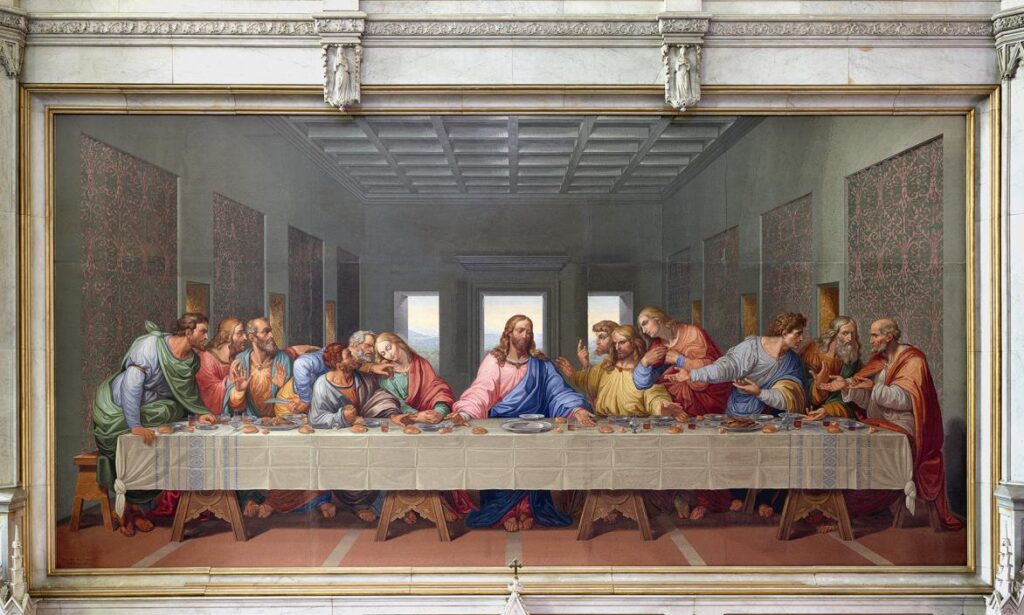

UN CAPOLAVORO UNICO

Ma il micromosaico non fu solo applicato su piccole tavolette, a Vienna nel 1817 Giacomo Raffaelli, il più grande mosaicista dell’epoca, inizialmente presso lo Studio Vaticano e poi con bottega personale a Roma, terminò di realizzare un enorme micromosaico rappresentate una copia dell’Ultima Cena di Leonardo. Un’opera d’arte grande come l’originale e destinata al Louvre lunga 9,18 metri e alta 4,47 metri, commissionata nel 1807 da Eugène de Beauharnais, figlio della prima moglie di Napoleone. I lavori furono compiuti a Milano e durarono fino al 1817. Attualmente il mosaico si trova a Vienna nella chiesa dei Minoriti, punto di riferimento della comunità italiana della città.

A UNIQUE MASTERPIECE

But micromosaic was not only applied to small tablets. In Vienna, in 1817, Giacomo Raffaelli, the greatest mosaic artist of the time, initially at the Vatican Mosaic Studio and later with his own workshop in Rome, completed a huge micromosaic representing a copy of Leonardo’s Last Supper. This artwork is as large as the original and was destined for the Louvre, measuring 9.18 meters in length and 4.47 meters in height. It was commissioned in 1807 by Eugène de Beauharnais, the son of Napoleon’s first wife. The work was carried out in Milan and lasted until 1817. Currently, the mosaic is located in Vienna, in the church of the Minorites, a landmark for the Italian community in the city.

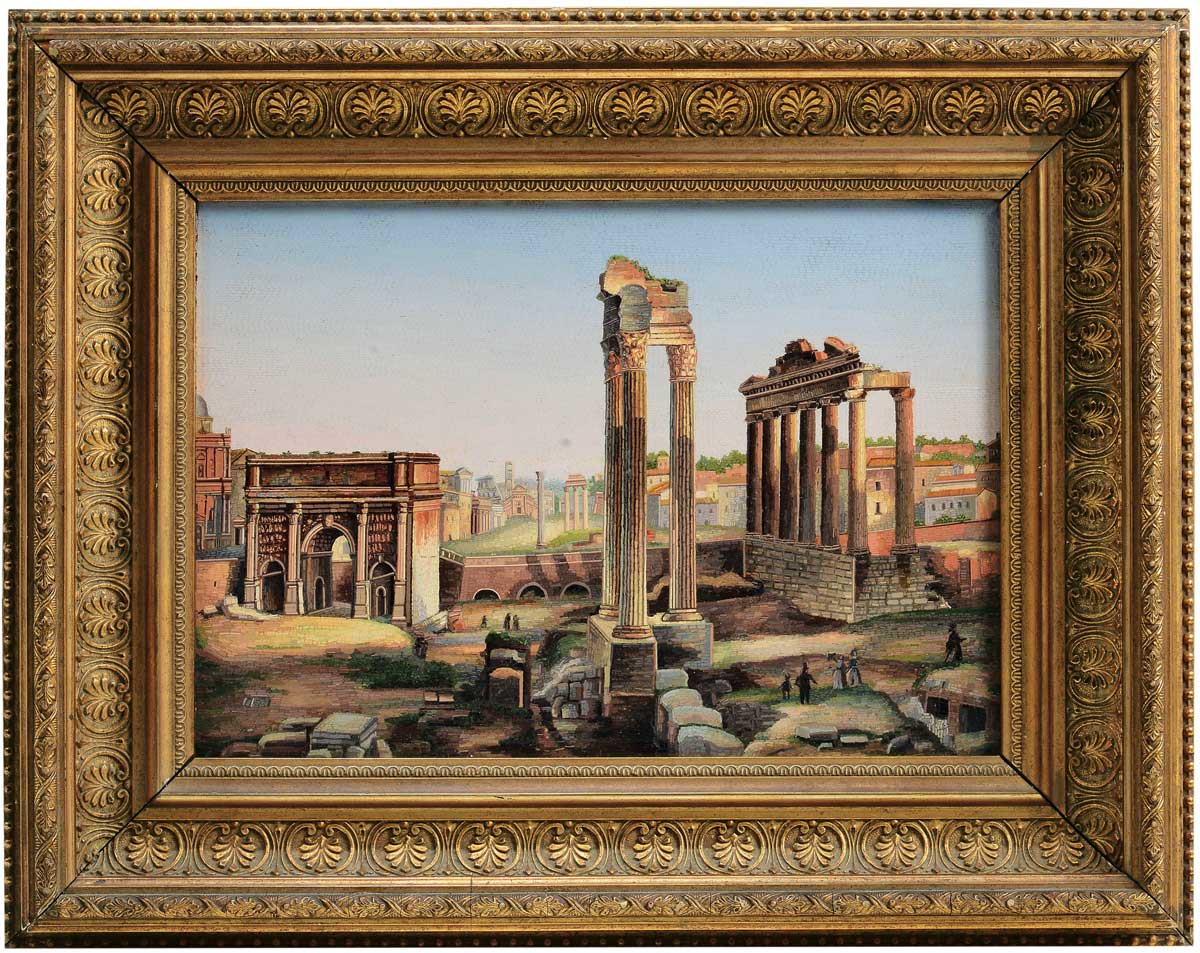

IL GRAND TOUR

Quasi contemporaneamente assistiamo a un’espansione del “Grand Tour”, di cui Goethe fu uno dei principali protagonisti, il lungo viaggio nell’Europa continentale effettuato da eredi di nobili casate aristocratiche, spesso affiancati da meno blasonati, ma spesso più facoltosi, figli della classe borghese. Le destinazioni principali erano la Francia, l’Olanda la Germania, ma l’obiettivo privilegiato era l’Italia con le sue principali città, Roma in particolare. Le nuove scoperte archeologiche a Ercolano, Pompei e Paestum furono un ulteriore richiamo per quella schiera fitta e eterogenea di “turisti” stranieri. Verso la fine del ‘700 ogni uomo di cultura europeo che si rispettasse doveva aver compiuto almeno un viaggio in Italia, paese ricco di testimonianze del passato classico e cornice di splendidi capolavori. Questo boom si protrasse fino all’’800 con il nome di “Grand Tour”: termine coniato per la prima volta nel 1670 dall’ inglese Richard Lassel nel suo libro “ Voyage of Italy, or a complete Journey through Italy”, la prima “guida” di grande diffusione che turisti si portavano utilmente appresso.

A quei tempi la fotografia non esisteva ancora e per le loro “memorie visive” i viaggiatori si affidavano a pittori e disegnatori ma è evidente che davanti a tanto turismo di lusso e proprio per soddisfare la sua sempre maggiore richiesta di “souvenirs” i mosaicisti romani iniziarono a produrre un’infinita varietà di oggetti in micromosaico estremamente raffinati, aventi come soggetti i luoghi famosi di Roma: Piazza san Pietro, Fori Imperiali, Pantheon.

THE GRAND TOUR

Almost simultaneously, we witness an expansion of the “Grand Tour,” of which Goethe was one of the main protagonists – the extensive journey across continental Europe undertaken by heirs of noble aristocratic houses, often accompanied by less distinguished but wealthier sons of the bourgeois class. The main destinations were France, the Netherlands, and Germany, but the preferred objective was Italy, with its major cities, particularly Rome. The new archaeological discoveries in Herculaneum, Pompeii, and Paestum were an additional attraction for this diverse and dense group of foreign “tourists.” Towards the end of the 18th century, every cultured European man of respectability was expected to have undertaken at least one journey to Italy, a country rich in classical past testimonies and the backdrop for splendid masterpieces. This boom continued into the 19th century under the name of the “Grand Tour,” a term first coined in 1670 by the Englishman Richard Lassel in his book “Voyage of Italy, or a complete Journey through Italy,” the first widely distributed “guide” that tourists conveniently carried with them.

At that time, photography did not yet exist, and for their “visual memories,” travelers relied on painters and illustrators. However, faced with such luxury tourism and to meet the growing demand for “souvenirs,” Roman mosaicists began to produce an infinite variety of extremely refined micromosaic objects. These items featured famous Roman locations such as St. Peter’s Square, the Imperial Forums, and the Pantheon.

GLI ATELIERS ROMANI

Già sul finire del ‘700 Piazza di Spagna e le vie adiacenti, luoghi preferiti dai viaggiatori stranieri che soggiornavano in città, si riempirono di ateliers specializzati in questa arte, tra questi quello di Giacomo Raffaelli, Nicola Roccheggiani, Nicola De Vecchis e Antonio Aguatti; persino lo Studio Vaticano nel 1795 entrò nel florido mercato cittadino con una produzione di soggetti profani.

Proprio dai mosaicisti dei laboratori dello Studio Vaticano vennero realizzati degli splendidi gioielli in micromosaico, orecchini, spille, bracciali. Persino Goethe, nel suo “Italienishe reise” del 1786 citava: ” ……l’arte del mosaico, che agli antichi offriva i pavimenti, ai cristiani inarcava il cielo delle loro chiese, ora si è avvilita fino alle tabacchiere e ai braccialetti…….. “.

Fortunatamente Goethe si sbagliava nel disprezzare quella serie infinita di piccoli oggetti in micromosaico, piccoli capolavori, una vera e propria forma d’arte, realizzati da mani artisti famosi o anonimi. La breve durata di questa arte rende difficoltosa la datazione degli oggetti, considerando che ci fu una veloce sovrapposizione di stili e che, soprattutto, la maggior parte delle opere non vennero firmate poichè i mosaicisti non si sentivano creatori dell’opera ma semplici riproduttori.

Le opere in micromosaico, sempre più apprezzate, stanno raggiungendo notevoli quotazioni nelle attuali aste.

THE ROMAN WORKSHOPS

Already at the end of the 18th century, Piazza di Spagna and the adjacent streets, favored by foreign travelers staying in the city, were filled with specialized workshops in this art. Among these were the workshops of Giacomo Raffaelli, Nicola Roccheggiani, Nicola De Vecchis, and Antonio Aguatti. Even the Vatican Mosaic Studio entered the thriving city market in 1795 with a production of secular subjects.

Indeed, it was the mosaicists from the workshops of the Vatican Mosaic Studio who created splendid micromosaic jewelry, including earrings, brooches, and bracelets. Even Goethe, in his “Italian Journey” of 1786, mentioned: “…the art of mosaic, which once offered pavements to the ancients and arched the sky of their churches for Christians, has now fallen to the level of snuffboxes and bracelets…”.

Fortunately, Goethe was mistaken in disparaging this endless series of small micromosaic objects—small masterpieces and a true form of art, crafted by the hands of both famous and anonymous artists. The brief lifespan of this art makes dating objects challenging, considering the rapid overlapping of styles and, most importantly, that the majority of works were not signed because mosaicists did not see themselves as creators but merely reproducers.

Micromosaic works, increasingly appreciated, are now achieving significant prices in contemporary auctions.

©Giusy Baffi aggiornato al 2022 (prima pubblicazione su Cose Antiche n. 182 marzo 2008 e parzialmente su ArteVitae.it dicembre 2018)

© Le foto sono state reperite da libri e cataloghi d’asta o in rete e possono essere soggette a copyright. L’uso delle immagini e dei video sono esclusivamente a scopo esplicativo. L’intento di questo blog è solo didattico e informativo. Qualora la pubblicazione delle immagini violasse eventuali diritti d’autore si prega di volerlo comunicare via email a info@giusybaffi.com e saranno prontamente rimosse oppure citato il copyright ©.

© Il presente sito https://www.giusybaffi.com/ non è a scopo di lucro e qualsiasi sfruttamento, riproduzione, duplicazione, copiatura o distribuzione dei Contenuti del Sito per fini commerciali è vietata.

© The photos have been sourced from books, auction catalogs, or online and may be subject to copyright. The use of images and videos is solely for explanatory purposes. The intent of this blog is purely educational and informational. If the publication of images were to violate any copyright, please communicate this via email to info@giusybaffi.com, and they will be promptly removed or the copyright © will be cited.

© The present website https://www.giusybaffi.com/ is not for profit, and any exploitation, reproduction, duplication, copying, or distribution of the Site’s Content for commercial purposes is prohibited.