ALTA COMMITTENZA, gli arredi in metallo del 1700 – HIGH COMMITMENT, the metal furniture from the 1700s.

Quando sentiamo parlare di mobili in metallo, pensiamo subito ad arredi per giardini, a letti in ferro battuto, lampadari o a modernissimi arredi di design. Nulla di più sbagliato.

Tra la fine del 1700 e i primi del 1800 vengono realizzati, imitando i mobili tradizionali in legno, splendidi mobili in metallo, eseguiti in bronzo, in argento e persino in acciaio.

Si tratta di mobili estremamente rari e solo pochissimi esemplari sono giunti fino a noi, mobili di alta committenza, veri e propri modelli unici nati per stupire, per impreziosire le wunderkammer (la stanza delle meraviglie) delle Corti.

Soprattutto sono il frutto di una grandissima abilità e di un’altissima qualità da parte dei migliori disegnatori, scultori, cesellatori, fabbri e maestri fusori dell’epoca.

LA REINTERPRETAZIONE DEGLI STILI DI FINE ‘700 E PRIMI ‘800

Alcuni mobili riprendono, anche se con lievi rielaborazioni, lo stile Luigi XVI, stile essenziale ma mai severo, come la stupenda coppia di tavolini interamente in rame dorato con piano in legno pietrificato realizzata alla fine del ‘700 a Firenze dalla Galleria dei Lavori (ora Opificio delle Pietre Dure) per gli Asburgo – Lorena granduchi di Toscana.

When we hear about metal furniture, we immediately think of garden furnishings, wrought iron beds, chandeliers, or very modern designer pieces. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Between the late 1700s and the early 1800s, splendid metal furniture was crafted, imitating traditional wooden furniture, made in bronze, silver, and even steel.

These are extremely rare pieces, and only very few examples have survived to this day. They were commissioned by high-ranking individuals, true unique models created to amaze and enrich the “wunderkammer” (the room of wonders) of the Courts.

Above all, they are the result of great skill and high-quality craftsmanship by the best designers, sculptors, engravers, blacksmiths, and master smelters of the time.

THE REINTERPRETATION OF LATE 1700s AND EARLY 1800s STYLES

Some of these pieces draw inspiration, with slight modifications, from the Louis XVI style, which is essential but never severe. For example, the stunning pair of tables entirely made of gilded copper with a petrified wood top, created at the end of the 18th century in Florence by the Galleria dei Lavori (now Opificio delle Pietre Dure) for the Habsburg-Lorraine grand dukes of Tuscany.

Sempre a Firenze, agli inizi dell’ 800, su commissione della sorella di Napoleone Elisa Baciocchi, Principessa di Lucca e Piombino e poi Granduchessa di Toscana, l’argentiere Andrea Marchesini realizza presso la Galleria dei Lavori di Firenze, uno splendido tavolo da gioco in stile Impero con piano in pietre dure, traducendo in bronzo un disegno di Fontaine.

In Florence, at the beginning of the 19th century, commissioned by Napoleon’s sister, Elisa Baciocchi, Princess of Lucca and Piombino, and later Grand Duchess of Tuscany, the silversmith Andrea Marchesini created a magnificent Empire-style gaming table with a hardstone top at the Galleria dei Lavori in Florence. This table was crafted in bronze, translating a design by Fontaine.

SCHINKEL, THOMIRE E GLI ALTRI

Altri mobili vengono commissionati ad architetti come Karl Friedric Schinkel in Germania, a scultori del calibro di Pierre Philippe Thomire in Francia, del quale possiamo vedere uno splendido tavolo interamente in bronzo dorato con piano in malachite datato 1819 (ora a Palazzo Pitti) in un ridondante stile impero, realizzato per Nicola Demidoff, pronipote dello zar Pietro il Grande e ambasciatore di Russia presso la Corte Toscana.

SCHINKEL, THOMIRE, AND OTHERS

Other furniture pieces were commissioned from architects like Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Germany and sculptors of the caliber of Pierre Philippe Thomire in France. One outstanding example is a splendid table entirely made of gilded bronze with a malachite top, dating back to 1819 (now at Palazzo Pitti) in a lavish Empire style. This table was created for Nicola Demidoff, the great-grandson of Tsar Peter the Great and the Russian ambassador to the Tuscan Court.

Al Getty Museum di Los Angeles possiamo ammirare una splendida console in stile tardo Luigi XV e con un anticipo dello stile Luigi XVI, in acciaio e bronzo dorato con piano in marmo Blue Turquin datata tra il 1765 e il 1769 disegnata dall’architetto Victor Louis su commissione di Stanislao Augusto II re di Polonia, per il palazzo reale di Varsavia e realizzata da Pierre Deumier serrurier du Roi ovvero fabbro della Real Casa francese.

At the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, you can admire a splendid console table in the late Louis XV style with a hint of Louis XVI, made of steel and gilded bronze with a Blue Turquin marble top. This console table is dated between 1765 and 1769 and was designed by the architect Victor Louis, commissioned by Stanislaus Augustus II, the King of Poland, for the Royal Palace in Warsaw. It was crafted by Pierre Deumier, the “serrurier du Roi,” or the locksmith of the French Royal House.

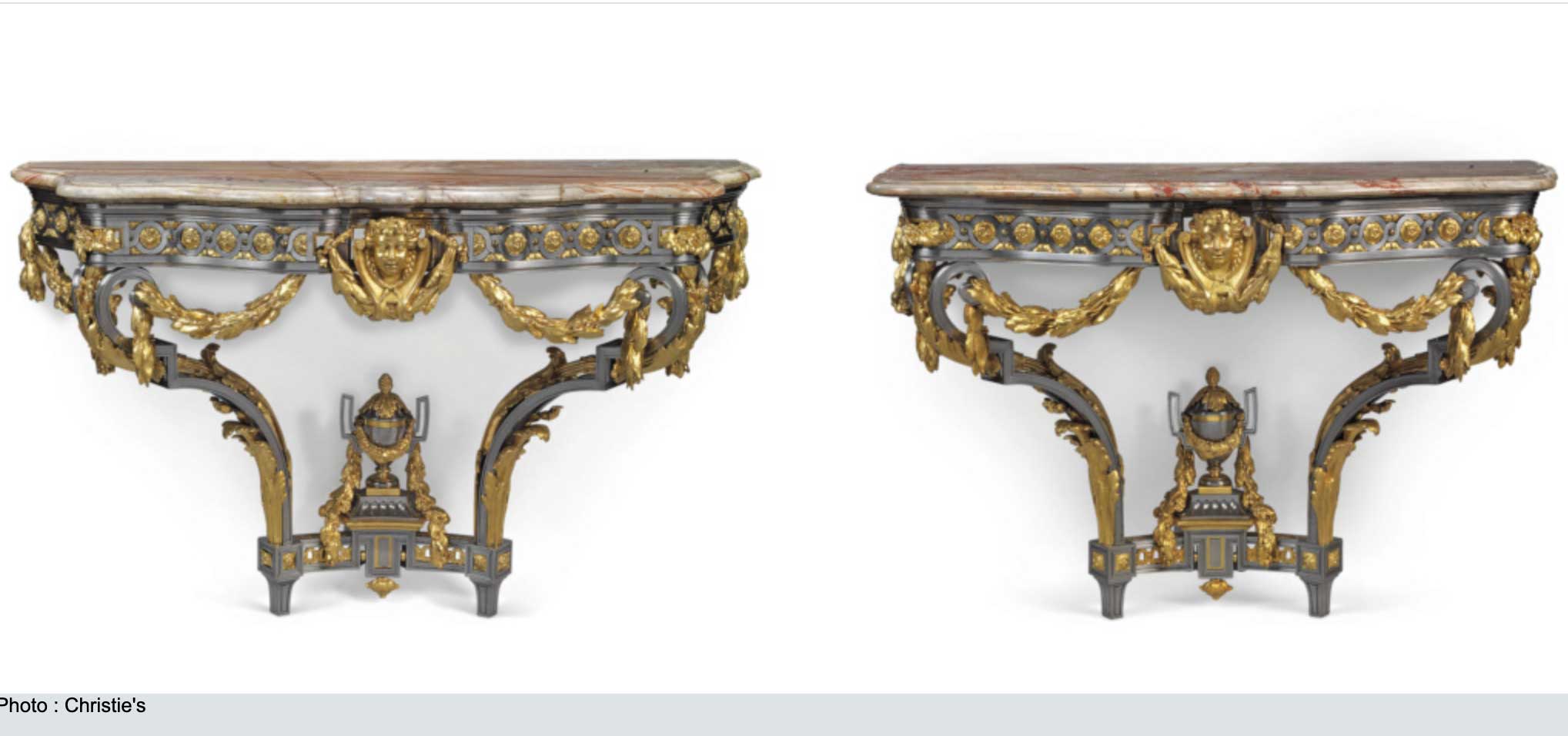

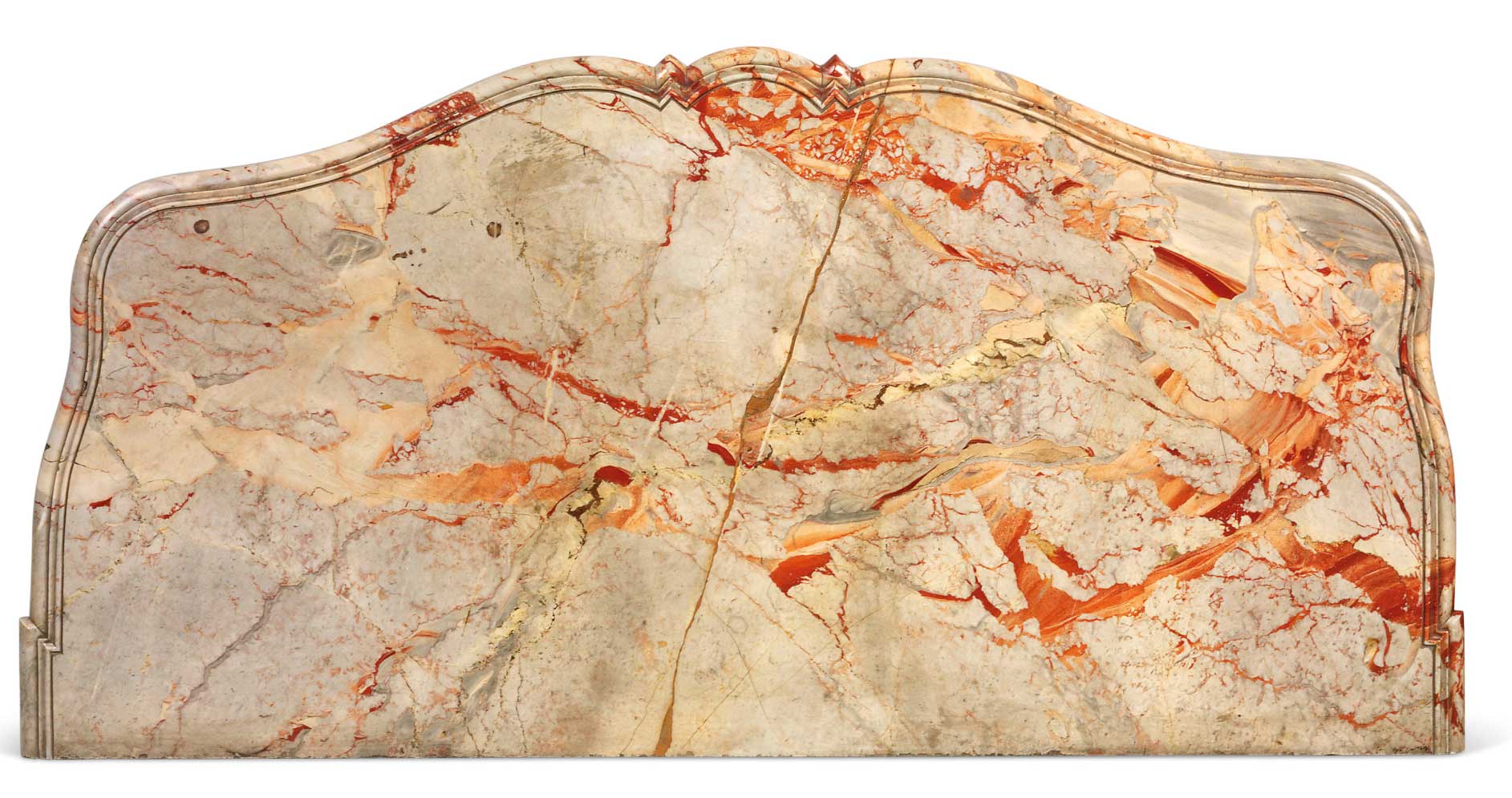

Altre due consoles appartenenti alla stessa serie in acciaio e bronzo dorato ma impreziosite da un marmo Sarrancolin e provenienti dalla Collezione Rothschild, sono state battute dalla casa d’aste Christie’s nel 2019 per la cifra di 2,831,250 sterline.

Two more consoles from the same series, made of steel and gilded bronze but adorned with Sarrancolin marble, and originating from the Rothschild Collection, were auctioned by Christie’s in 2019 for a sum of 2,831,250 pounds.

Altrettanto stupefacente è lo straordinario guéridon con piano di legno pietrificato incastonato in una cornice e treppiede di acciaio lucido e bronzo dorato eseguito dall’orafo di corte Anton Matthias Domanöck (1713-1779), commissionato dalla sorella maggiore di Maria Antonietta, Maria Cristina, duchessa di Sassonia-Teschen, e consegnato a Versailles come dono alla delfina nell’anno del suo matrimonio, avvenuto nel 1770.

Equally astonishing is the extraordinary guéridon with a petrified wood top set within a frame and a polished steel and gilded bronze tripod base, crafted by the court goldsmith Anton Matthias Domanöck (1713-1779). This guéridon was commissioned by Maria Christina, the elder sister of Marie Antoinette, Duchess of Saxony-Teschen, and it was presented at Versailles as a gift to the dauphine in the year of her marriage in 1770.

E’ di manifattura russa un rarissimo tavolino in argento massiccio per il gioco degli scacchi, in stile Luigi XVI e databile nella prima metà del XIX secolo.

Il piano è formato da una scacchiera in pietre dure in agata, malachite, avventurina e sodalite. Le gambe dritte e rivestite in malachite sono unite tra di loro da un raccordo a forma di X in argento, al cui centro è posizionato un vaso in agata con fiori in argento. I piedi sono in argento con cesellate delle foglie d’acanto.

A truly rare piece of Russian craftsmanship is a solid silver chess table, made in the style of Louis XVI and dating back to the first half of the 19th century.

The tabletop features a chessboard made of semi-precious stones, including agate, malachite, aventurine, and sodalite. The straight legs, covered in malachite, are connected by a silver X-shaped support, with a central agate vase adorned with silver flowers. The feet are made of silver with intricately engraved acanthus leaves.

A Parigi, al Museo d’Orsay, è possibile ammirare la toilette della duchessa di Parma, eseguita in argento e bronzo dal prestigioso gioielliere parigino François Froment-Meurice tra il 1845 e il 1848. I portagioielli, la cui forma ricorda i reliquari del XII secolo, sono decorati con i ritratti di venti donne francesi famose per la loro pietà, il loro coraggio e il loro talento letterario, come Bianca di Castiglia, Giovanna d’Arco o Clémence Isaure. La brocca e la vasca combinano fonti islamiche e rinascimentali, mentre i candelabri si ispirano a modelli in bronzo del XVII secolo. Lo stile indeciso dell’insieme manifesta in definitiva un eclettismo che dominerà successivamente le arti decorative sotto il Secondo Impero.

In Paris, at the Musée d’Orsay, you can admire the toilet set of the Duchess of Parma, crafted in silver and bronze by the prestigious Parisian jeweler François Froment-Meurice between 1845 and 1848. The jewelry caskets, reminiscent of 12th-century reliquaries, are adorned with portraits of twenty famous French women known for their piety, courage, and literary talent, such as Blanche of Castile, Joan of Arc, or Clémence Isaure. The pitcher and basin combine Islamic and Renaissance influences, while the candlesticks draw inspiration from 17th-century bronze models. The overall style of the ensemble ultimately reflects an eclectic approach that would later dominate decorative arts during the Second Empire.

I MOBILI DI ACCIAIO DI TULA

Un discorso a parte va doverosamente fatto per i mobili in acciaio eseguiti a Tula in Russia e commissionati da Caterina II per i suoi palazzi a San Pietroburgo.

Agli inizi del 1700 lo zar Pietro I di Russia, impegnato non solo in una lunga guerra contro la Svezia per il controllo del mar Baltico, ma anche contro gli Ottomani, decide di trasferire i migliori armaioli del suo impero a Tula, una città di origine medievale situata nella Russia centrale, sul fiume Opa a 165 chilometri da Mosca.

Viene così fondato l’arsenale imperiale permanente.

L’utilizzo dell’acciaio per la fabbricazione delle armi e il gran numero di artigiani armaioli presenti sul territorio, fecero in modo che nel giro di pochissimo tempo gli artigiani di Tula iniziassero una produzione in acciaio di oggetti di uso quotidiano, decorandoli con le stesse tecniche usate per le armi più preziose: cesellatura, intarsiatura e brunitura.

Intorno al 1730 iniziarono a produrre, per ovvii motivi bellici, mobili da campo pieghevoli in acciaio imitando lo stile dei mobili in legno.

Nell’arco di pochissimo tempo gli elementi decorativi diventarono sempre più elaborati, iniziarono le decorazioni a rilievo, con ceselli a ghirlande, nastri, trafori, trattandole anche con bagni dorati al mercurio; venne messa a punto una tecnica molto particolare: quella della sfaccettatura a diamante dell’acciaio.

THE STEEL FURNITURE OF TULA

A special mention must be made for the steel furniture crafted in Tula, Russia, commissioned by Catherine II for her palaces in St. Petersburg.

In the early 1700s, Tsar Peter I of Russia, engaged not only in a protracted war against Sweden for control of the Baltic Sea but also against the Ottomans, decided to relocate the best gunsmiths of his empire to Tula, a medieval city located in central Russia on the Opa River, 165 kilometers from Moscow.

This led to the establishment of a permanent imperial arsenal.

The use of steel for weapon manufacturing and the large number of gunsmith artisans in the area soon resulted in Tula craftsmen producing steel objects for everyday use. They decorated these objects using the same techniques as for the finest weapons: engraving, inlaying, and bluing.

Around 1730, they began producing folding steel camp furniture, primarily for military purposes, imitating the style of wooden furniture. Over time, the decorative elements became more elaborate, with relief decorations, garlands, ribbons, fretwork, and treatments with mercury gilding. They also developed a distinctive technique: diamond faceting of the steel.

Le bruniture si fecero sempre più sofisticate e realizzate in vari colori, dal verde al lilla passando per il rosa e l’azzurro; all’acciaio venivano aggiunti oro e argento e i pezzi che uscivano da quelle botteghe, solitamente pezzi unici, erano talmente belli e preziosi che affascinarono Caterina II al punto che li commissionò per i suoi palazzi a San Pietroburgo.

La loro struttura imitava, anche se in maniera rivisitata, il gusto neoclassico di moda in Europa, lo stile Luigi XVI in Francia e lo stile Adam in Inghilterra.

Questi mobili, proprio perché unici e pregiati, divennero ambiti da tutta l’aristocrazia russa.

Al Metropolitan Museum di New York è esposto in tutta la sua bellezza, la summa del mobile prodotto a Tula: uno splendido tavolino in acciaio, con la tipica lavorazione a diamanti e bronzi dorati al mercurio.

The bluing techniques became increasingly sophisticated and were executed in various colors, ranging from green to lilac, passing through pink and blue. Gold and silver were added to the steel, and the pieces that came out of those workshops, often unique works of art, were so beautiful and precious that they captivated Catherine II to the point that she commissioned them for her palaces in St. Petersburg.

Their structure, though with a reinterpretation, imitated the neoclassical taste fashionable in Europe, including the Louis XVI style in France and the Adam style in England.

These furniture pieces, precisely because they were unique and highly esteemed, became sought after by the entire Russian aristocracy.

On display at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in all its beauty is the epitome of furniture produced in Tula: a splendid steel coffee table with the characteristic diamond-pattern work and gilded mercury bronze accents.

A San Pietroburgo, al Museo del Palazzo Pavlovsk, si trovano diversi mobili di Tula, tra questi spiccano una splendida toelette in acciaio con intarsi in acciaio con lavorazione a diamante, un tavolo con poggiapiedi in acciaio lucido e sfaccettato e bronzo dorato e cesellato, dono dello zar Alessandro I alla madre Maria Fedorovna nel 1801 e una sedia con poggiapiedi del 1789 in acciaio lucido sfaccettato e bronzo cesellato e dorato.

Al Museo Statale dell’Ermitage di San Pietroburgo, è possibile trovare un’altra sedia in acciaio con una lavorazione simile, anch’essa rappresentativa dell’arte e dell’abilità dei mobili in acciaio di Tula.

In St. Petersburg, at the Pavlovsk Palace Museum, you can find several pieces of Tula furniture, among which stand out a magnificent steel dressing table with diamond-pattern steel inlays, a table with polished and faceted steel legs and gilded and chased bronze, given by Tsar Alexander I to his mother Maria Fedorovna in 1801, and a chair with a footrest from 1789 made of polished, faceted steel and gilded and chased bronze.

At the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, you can find another chair in steel with a similar craftsmanship, also representing the artistry and skill of Tula steel furniture.

Infine a Londra, al Victoria and Albert Museum, si può ammirare un grande camino con parafuoco formato da migliaia di singoli elementi in acciaio, prodotto a Tula alla fine del XVIII secolo.

Finally, in London, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, you can admire a large fire screen made up of thousands of individual steel elements, produced in Tula at the end of the 18th century.

Dopo la morte di Caterina di Russia, avvenuta nel 1796, questa moda si interruppe e, nel 1808 durante le guerre napoleoniche, Tula, per ordine del ministero della Guerra, dovette smettere la produzione di oggetti d’arte per concentrarsi solo sulla produzione di armi.

A guerra terminata, la magia degli artigiani di Tula era finita, come pure la moda dei mobili d’acciaio, e si produssero solo banali oggetti di uso quotidiano.

After the death of Catherine the Great of Russia in 1796, this fashion came to an end. In 1808, during the Napoleonic Wars, Tula was ordered by the Ministry of War to cease the production of art objects and focus solely on producing weapons.

Once the war was over, the enchantment of Tula’s craftsmen had faded, as had the fashion for steel furniture. Only ordinary everyday objects were produced from that point onward.

©Giusy Baffi aggiornato 2023 – (pubblicato su L’Esperto Risponde – n. 47 / 2007 – pubblicato su ArteVitae.it 11 febbraio 2019)

Fonti:

Colle, Grisieri, Valeriani, Bronzi decorativi in Italia, Electa Edizioni

A.A.V.V. Château de Versailles Catalogo Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Parigi 2008, cat.n° 239 2007

Antoine Chenevièr, Il mobile russo, Leonardo Edizioni

A.A.V.V. ZAR State Historical Museum, Lybra Immagine Edizioni

A.A.V.V. Le Mobilier du Musée du Louvre

CHRISTIE’S LONDON, Masterpieces from a Rothschild Collection 2019

© Le foto sono state reperite da libri e cataloghi d’asta o in rete e possono essere soggette a copyright. L’uso delle immagini e dei video sono esclusivamente a scopo esplicativo. L’intento di questo blog è solo didattico e informativo. Qualora la pubblicazione delle immagini violasse eventuali diritti d’autore si prega di volerlo comunicare via email a info@giusybaffi.com e saranno prontamente rimosse oppure citato il copyright ©.

© Il presente sito https://giusybaffi.com/ non è a scopo di lucro e qualsiasi sfruttamento, riproduzione, duplicazione, copiatura o distribuzione dei Contenuti del Sito per fini commerciali è vietata.

©Photos have been sourced from books and auction catalogs or online and may be subject to copyright. The use of images and videos are for explanatory purposes only. the purpose of this blog is only educational and informative.This website and blog claim no credit for any image posted unless otherwise noted. Images on this website and blog are copyrighted to its respectful owners. If there is an image appearing on this blog and website that belongs to you and do not wish for it to appear on this site, please email to info@giusybaffi.com and it will be promptly removed or copyright © cited.

© This site https://giusybaffi.com/ is not for profit and any exploitation, reproduction, duplication, copying or distribution of the Site Content for commercial purposes is prohibited.